It's been 10 years since the stock market bottomed out in the wake of the financial crisis: In March 2009, many major players in the financial industry were brought to their knees. While some have turned things around nicely, others still face problems -- or no longer exist in the same form.

Here are three major financial institutions that were particularly hard-hit by the financial crisis, how they're doing today, and how shareholders have fared in the decade since the market hit bottom.

Image source: Getty Images.

1. Bank of America: A true turnaround story

Bank of America's (BAC 0.59%) crisis-era problems can mainly be attributed to its acquisitions of credit card giant MBNA in 2005 and mortgage originator Countrywide Financial in 2008. The short version is that MBNA's loan portfolio produced massive write-offs when the economy turned sour and, to put it mildly, Countrywide's underwriting standards and general business practices weren't as sound as they appeared.

Ultimately, Bank of America paid more than $91 billion in penalties and settlements by 2015, and that's in addition to its portfolio losses.

This story does have a happy ending, however: Bank of America has successfully transformed itself into one of the best-run and most profitable of the big U.S. banks. The company's return on equity (ROE) and return on assets (ROA) are well above industry benchmarks, loan losses are low, efficiency is on par with the other big banks, and Bank of America has emerged as a leader in banking technology.

Prior to the financial crisis, Bank of America's stock regularly traded for over $50 per share. The bank was forced to dilute shareholders by issuing 3.5 billion new shares to build up its capital, and the stock hit bottom at just over $3 per share in March 2009. Since then, however, Bank of America has generated a 734% total return for shareholders, making it one of the best-performing U.S. bank stocks in the postcrisis era.

2. Wachovia: How Wells Fargo was catapulted into the "big four"

At the end of 2008, Wachovia was the fourth-largest U.S. bank. Unfortunately, thanks to risky mortgage loans (many of which resulted from acquisitions, not the bank's own underwriting), it started to experience massive losses. In the second quarter of 2008 alone, Wachovia reported a loss of $8.9 billion.

As a result of large-scale withdrawals by depositors and the failure of Washington Mutual, regulators encouraged Wachovia to attempt to sell itself. Many people don't realize or remember that Citigroup was the original buyer for Wachovia's retail banking operations, for the rock-bottom price of about $1 per share.

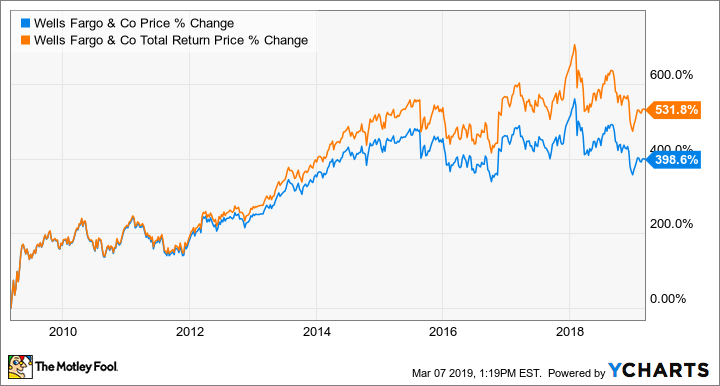

Shareholders were unhappy with the low price, and Wells Fargo (WFC +0.37%) swooped in and made a better offer with no government involvement. In the all-stock transaction, Wells Fargo paid the equivalent of about $7 per share for the banking giant ($15.1 billion in total) -- an absolute bargain for such a massive institution, one that had been trading for about $50 per share just a year earlier. This acquisition is the main reason Wells Fargo is a national powerhouse today.

In the deal, investors received 0.1991 shares of Wells Fargo for each of their Wachovia shares. Assuming that they held on to those shares, they've received a total return of 531% since March 9, 2009. While Wachovia was sold at a fire-sale valuation, its stock wasn't nearly as diluted as was the case with some other institutions; shareholders who maintained their position are surprisingly almost back to even, when considering Wachovia's precrisis highs.

Check out the latest earnings call transcripts for Bank of America, AIG and other companies we cover.

3. AIG: The classic "too big to fail" case

At the time of the financial crisis, American International Group (AIG 3.17%) was the world's largest insurance company. Unfortunately, losses on its mortgage-related investments and some other assets led to major liquidity concerns by the fall of 2018, and the company's survival was questionable. It was ultimately decided that AIG was "too big to fail," so the federal government authorized a series of massive credit lines to keep the company afloat.

AIG proceeded to shed some of its assets in order to reduce leverage and raise capital, and the company paid back all of its government assistance by March 2013.

As for its stock price, AIG has recovered nicely but still trades at a (split-adjusted) fraction of its precrisis levels. Since bottoming out in March 2009, AIG has generated a total return of nearly 700% for shareholders.

We could go on...for a long time

Between 2008 and 2012, there were 465 banks that failed. To cite some well-known examples, Lehman Brothers didn't survive, and Bear Stearns and Washington Mutual were acquired by stronger financial institutions. Countless others survived only with government help; Citigroup, whose situation was similar to that of Bank of America, was among this group.

The point is that this isn't an exhaustive list by any means. The stories above are simply three interesting examples of how some of the United States' major financial institutions (and their shareholders) have done since the market hit bottom a decade ago.