Unlike oil, natural gas has historically been priced as a regional product. That means there can be wide price spreads for gas around the world. Thanks to the recent glut of production in the U.S., gas is really cheap at home. Many think that if we can liquefy natural gas, transport it across the ocean, and regassify it at various markets around the world at a cost below their current prices, then we can create a whole new market for U.S. gas.

The theory of natural gas exports sounds great. Let's examine why the challenges exporting natural gas faces may make it more difficult.

The theory

At first glance, the idea of selling our cheap gas to global markets looks very attractive. The top 10 importers of natural gas consume about 511 billion cubic meters of gas, or about 18 trillion cubic feet.

|

Country |

Imports |

Exports |

Net Imports |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Japan |

109.9 |

0 |

109.9 |

|

Italy |

70.37 |

0.12 |

70.25 |

|

Germany |

87.57 |

19.7 |

67.8 |

|

South Korea |

46.83 |

0 |

46.83 |

|

Turkey |

43.9 |

0.71 |

43.2 |

|

France |

47.04 |

5.38 |

41.6 |

|

United Kingdom |

53.43 |

16.7 |

36.7 |

|

Ukraine |

36.4 |

2.6 |

33.8 |

|

Spain |

35.49 |

1.7 |

33.8 |

|

China |

31.37 |

3.21 |

28.2 |

Source: CIA World Factbook (2011 estimates)

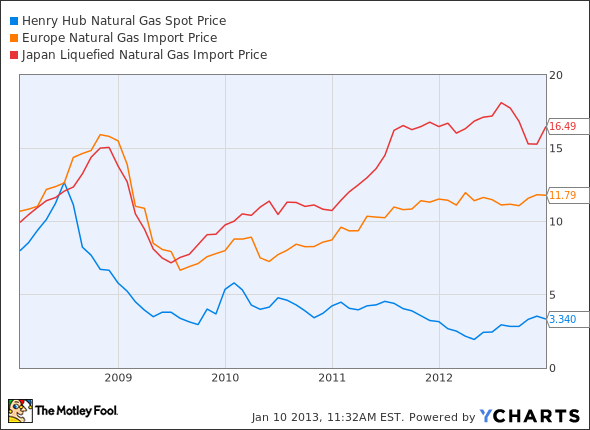

For exports to work, producers need a large enough difference between prices at the source and prices abroad. Spot prices in the U.S., Japan, and Europe seem to present just such an opportunity. Henry Hub spot price, the predominant standard for U.S. gas prices, sells at a discount of $8.34 per million BTUs and $13.15 per million BTUs to European and Japanese spot prices, respectively.

Henry Hub Natural Gas Spot Price data by YCharts

So, theoretically, the move to export natural gas makes sense, and several players have lined up to take advantage. Apache (APA 0.20%), and Chevron are collaborating to build an export terminal in British Columbia, and ExxonMobil and Dominion Resources have partnered up on an East Coast project and are awaiting a permit to export liquid natural gas, or LNG, from the U.S.

There are two players who already have a leg up: Cheniere Energy (LNG +1.23%) and InterOil (NYSE: IOC). Cheniere has the only permit in the U.S. to export natural gas to countries we do not have a free trade agreement with, and its second facility is next in line for permits. InterOil is in a unique position because it is working on developing natural gas fields and an LNG export facility in Papua New Guinea. Now that the local government has taken a large stake in the company, it might help InterOil move the export process along more quickly.

The reality

Here are three key points that make exporting less attractive than it sounds:

1. Processing costs: To transport natural gas in a commercially viable way, you have to convert it to liquid form by refrigerating it to about -260°F, transport it in a cryogenic tanker, and bring it back to a gaseous state at its final destination. Each of these steps is very costly in comparison to transporting other fossil fuels like coal and oil. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, or EIA, the added cost for the whole process can exceed $3.14 per million BTUs, depending upon the final destination. This doesn't include any import or export tariffs that may exist, nor the costs to build out an infrastructure to export. Each small increase in cost brings imported gas closer in price to local sources, and reduces the commercial feasibility of transporting natural gas.

2. Other potential sources: The price differential might be there today, but how long will it last? The U.S. was able to unlock so much natural gas because advances in new drilling technology have made it commercially viable to tap unconventional sources. But we aren't the only ones sitting on shale gas. A recent EIA Study shows that many of the largest importing countries have large shale deposits of their own.

Source: US Energy Information Agency

Of the 10 countries listed, only South Korea and Japan are not included in the study. Japan just successfully tapped its own shale oil field, and Russian giant Gazprom is working on a deal to export 10 billion cubic meters -- or about 1 billion cubic feet per day -- of gas per year to South Korea.

If countries start to tap into their own unconventional sources, it is very likely that their import demands will drop, and spot prices in these countries will probably follow suit.

3. The catch-22: The high cost of processing means that overseas prices need to stay high and local prices need to remain low, but if new sources of natural gas are delivered to these overseas markets via tanker, the price will drop in that market and the spot price margin will narrow. So by bringing natural gas closer to a global market, LNG exporters could wreak havoc on their own profit margins.

What a Fool believes

There is an opportunity in the LNG transportation business; it just may not be the magic wand for the natural gas market, as some might hope. Exploration and production companies would like to believe that LNG exports will raise local prices, but the benefits may not be as great as originally thought. A recent study by Deloitte estimates that by opening LNG exports to about 6 billion cubic feet per day, the average price for 1 million BTUs of natural gas will only increase by $0.15 -- hardly enough of an incentive to expand drilling operations. The 6 bcfd used in the study is equal to the total production of Cheniere's Sabine Pass facility, the only plant in the U.S. allowed to export LNG carte blanche.

So could more export capacity bring up prices? Possibly, but the timeline for those facilities to come online is so far out it is difficult to predict the outcome.

Cheniere was a first mover in the industry, and shrewdly locked in 20-year contracts for its LNG facility in Louisiana. If anyone can make a profit off of this venture, Cheniere's in the best position to do so right now.