Among Whole Foods Market's (WFM) operating statistics, comparable-store sales have always figured prominently for investors. Through fiscal year 2014, the company had maintained an outstanding 15-year average of 8% "comps" growth.

Yet fiscal 2015's narrative hasn't kept pace. Comps have slumped versus prior years, and are forecasted by management to finish in the "low single digits" this year. This has cooled the dynamic steam engine that was once Whole Food's stock: The "WFM" ticker is down nearly 36% this year.

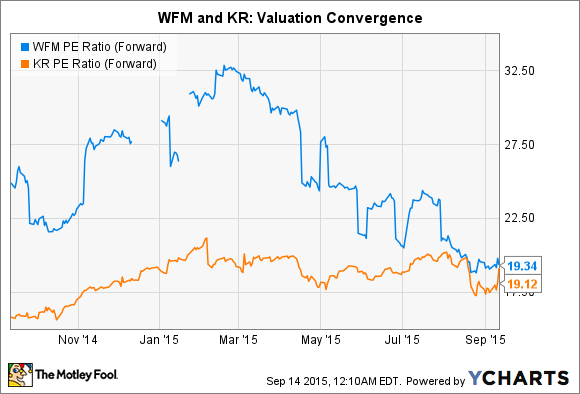

As a result, the stock's forward valuation has now converged with that of mammoth competitor Kroger Co., a low-margin, steady growth business that has actually outpaced Whole Foods in comps growth this year:

WFM P/E Ratio (Forward) data by YCharts.

Whole Foods investors fear the entry of Kroger and other large grocers into the company's former niche business of natural and organic foods. Yet to to parry competition, management won't necessarily respond with defensive pricing maneuvers.

Instead, Whole Foods' management team will likely lean on the improvement of a handful of financial measures that its board has isolated as key to the grocer's success. Most of these, at least conceptually, trace their implementation back to the late 1990s, during Whole Foods' first decade as a public company.

Two measures that create sustainable value

Given Whole Foods' organizational bent toward long-term sustainability, it's not surprising that net profit is an important, but not absolute, earnings metric. Instead, management favors a version of profit called "economic value added," or EVA, which it adopted in 1999. EVA measures net operating profit after taxes, reduced by a charge for the cost of invested capital required to produce the returns.

Using the company's weighted average cost of capital of 8% as a hurdle, management requires each new project (i.e. store opening) to return a cumulative positive EVA within five years. To look at this another way, Whole Foods won't invest in a store if it can't return an annual operating profit, after a deduction for taxes, of at least 8%.

A closely related concept is return on invested capital. ROIC measures financial returns against a capital base which includes not just assets, but also debt and equity. Because the calculation incurs many adjustments which can vary from industry to industry, there is no universally accepted formula to derive ROIC.

Whole Foods calculates ROIC by dividing adjusted earnings by its average invested capital base. ROIC can be improved by either increasing earnings, reducing the company's invested capital base, or both. At the end of fiscal Q3 2015, Whole Foods reported that it has generated a strong, trailing-52-week ROIC of 15.2%. The company has a near-term goal of exceeding 14% for fiscal 2015.

Together, these two measures encourage the creation of long-term value for shareholders. Using EVA instead of net profit as an earnings measure forces management to think twice about projected returns each time it considers a new store location. And maintaining a high ROIC target holds management accountable to using the company's capital as efficiently as possible.

Whole Foods Market in East Village, NYC. Source: David Shankbone under Creative Commons license.

Invest in margin before squeezing it

Since its fiscal 2014 annual report issued in November of last year, Whole Foods has warned that its gross margins, among the highest in the industry, will decline due to investments in technology, marketing, new stores, and its value pricing strategy (selective competitive pricing).

Yet so far, this margin compression really hasn't occurred. In the first three quarters of 2014, Whole Foods recorded a gross margin of 35.6%. Through the same period in the current year, gross margin stands at 35.4%.

While at some point shareholders will witness margin deterioration (I believe this will be on the order of 1 to 2 percentage points), management is clearly doing everything it can to further the investments mentioned above while giving up the minimum basis points of gross profit possible.

Letting margin drift would invariably hurt another metric dear to management's heart: EBITANCE, or earnings before interest, taxes, and non-cash expenses. Noncash expenses include depreciation, amortization, and the expense of stock awarded to employees. Rising EBITANCE relates back to the value creation measures above: Without a high earnings base (profitability), hitting EVA and ROIC goals becomes extremely difficult.

Comparables and positive free cash flow

Let's look briefly at two additional measures the C-suite seeks to improve. Despite the travails of the last year, Whole Foods executives likely believe that a long-term comps growth rate in the ballpark of its 15-year average of 8% is achievable. After all, competitor Kroger recorded 7 times the amount of Whole Foods' revenue in its most recent quarter, yet still hit comps growth of 5.3%. Thus, 6%-7% in the least is not unreasonable to expect from Whole Foods over the long haul.

Continuing to generate positive free cash flow is one way to lift comparable sales. Whole Foods paid off most of its long-term debt years ago, and essentially self-funds its growth. The company typically exhibits high cash flow relative to net income. In the first three quarters of fiscal 2015, Whole Foods has generated nearly $1 billion of operating cash flow, more than double the $479 million in net income recorded.

Positive free cash flow (excess cash left over from operations after making fixed asset expenditures) is cash that can be banked for future growth, once any other investing and financing activities, including dividends and share repurchases, are completed. Having "ready money" keeps expansion and store opening costs down, thus allowing the company to invest in comparable sales drivers.

Doubling down on these five measures

Burgeoning competition from well-heeled peers absolutely spearheads the current concerns surrounding Whole Foods. But executives won't be rewarded on how much market share the company wrests back from competitors.

They will, however, be rewarded on improvements in EVA, ROIC, EBITANCE, comparable-store sales growth, and positive free cash flow. Why? These are the quantitative criteria the board's compensation committee has set for the executive team's performance bonuses (in addition to other, qualitative criteria). Excepting Co-CEO John Mackey -- who has elected out of any bonus compensation and receives $1 per year of regular salary -- Whole Foods' management team will benefit from gains in any and all of these metrics.

By design then, the improvement of value creation, margin management, revenue growth, and free cash flow will mean that management has found the right strategies to address the competitive threats which are challenging Whole Food's business (and so worrying shareholders).

For example, the company's new "365 By Whole Foods Market" concept stores, opening next year, have been described by management as having a smaller footprint versus the average Whole Foods Store, potentially higher margins driven by lower labor costs, increased technology, less inventory (through a curated selection of goods), as well as requiring lighter capital investment.

Taken together, these characteristics can lift each of the five performance criteria above (although rising comps in "365" stores may come at the expense of flagship locations in proximity). In the end, management's response to competition is most likely to work with vigor on the goals that have always mattered to Whole Foods, rather than engaging in a knee-jerk, self-destructive pricing spiral to reengage customers.