Social Security is in desperate need of some changes. If things keep going as they are, the program will deplete the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance trust fund by late 2032, according to the most recent estimate from Social Security Chief Actuary Karen Glenn.

Once the trust fund falls to zero, Social Security is only legally allowed to pay out as much in benefits as it brings in. The actuarial team estimates that will be about 77% of benefits due in 2033, and it'll likely fall slightly through the end of the century.

Congress has the power to stave off benefit cuts, however, and many legislators have submitted proposals to the actuary's office to determine how they would impact the longevity of the government program that over 70 million Americans rely on for at least some of their income. Of course, it's one thing to theoretically solve Social Security's challenges and another to come up with legislation everyone in Congress can agree on.

Here's what could ensure that Social Security doesn't have to indiscriminately slash benefits and the program can continue through the end of the century (and beyond).

What's causing Social Security to go broke?

The short and simple answer to this question is that it's paying out more in benefits than it's collecting in revenue.

Social Security has three main sources of revenue:

- The Social Security tax on wages, a 12.4% flat tax (on up to $176,100 in wages in 2025).

- A portion of income taxes collected on Social Security benefits.

- Interest earned on bonds held in the Social Security trust funds.

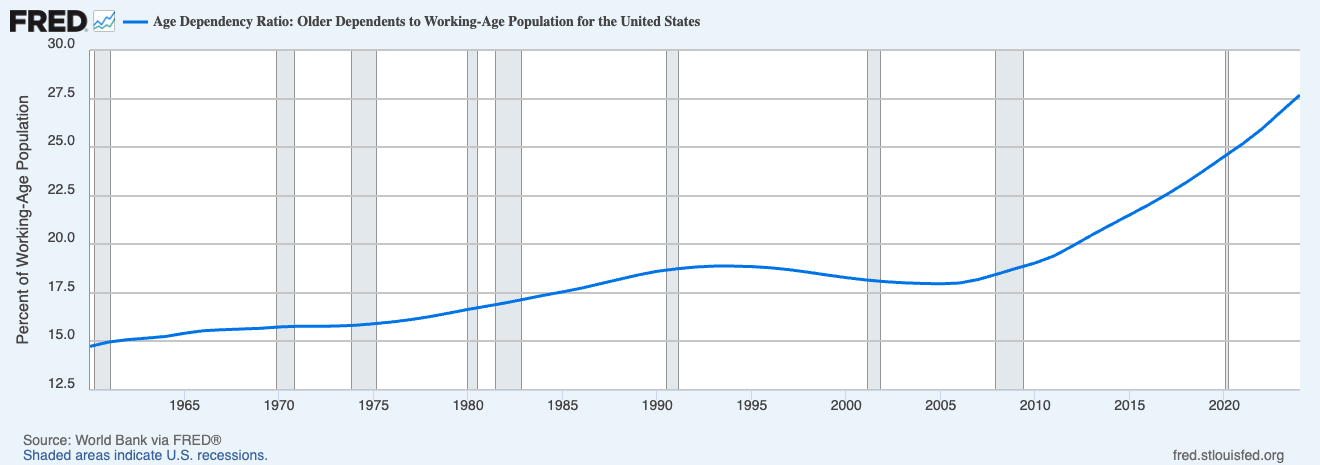

The U.S. finds itself facing a huge demographic shift, though, as the age dependency ratio (the number of Americans over 64 years old relative to the working age population) has shot higher over the last two decades. Baby boomers are retiring, and later generations are having fewer children. Combined with longer life expectancies, the shift finally caught up with Social Security earlier this decade.

After the trust fund balance peaked near the end of the last decade, this decade has seen an accelerating deficit for Social Security as it pays out more in benefits to more retirees every year. Properly fixing Social Security could require both retirees and workers to make sacrifices to ensure the program is there for those who need it in the future.

What can Congress do to save Social Security?

There are few proposals that would enact one simple change to overcome the entirety of Social Security's funding shortfall. Measures that do so are very extreme and unlikely to make it anywhere in Congress. As such, it'll require a combination of several changes to the program to make sure it lasts.

The equation to solve the shortfall is simple: increase revenue and reduce expenses. In other words, effective proposals are those that raise taxes or cut benefits -- neither being particularly popular with legislators or their constituents.

When it comes to raising taxes, some of the most reasonable proposals (in my opinion) involve taxing income above the current limit at the standard 12.4% rate and providing those workers with a slight bump in their primary insurance amount based on those taxed wages. This preserves the progressive nature of the program, ensuring lower-income workers don't see an increased tax burden.

A proposal to increase the maximum taxable wages to cover 90% of total earnings among Americans (where it was originally set in the 1980s) would eliminate 22% of the long-term shortfall. More-aggressive proposals to tax all earnings above $400,000 per year could eliminate as much as 57% of the shortfall.

Image source: Getty Images.

Reducing benefits can come in multiple forms. The way Congress has done it in the past was by increasing the full retirement age. This is effectively a benefit cut because claiming at the current full retirement age would result in a smaller monthly payment. If the law doesn't also change the rules for delayed retirement credits, it would also reduce the maximum possible benefit, since monthly benefits currently don't increase if you delay past age 70.

A proposal to increase the age for full benefits from 67 to 69 starting in 2026 and ending by 2033, while increasing the maximum age to earn delayed retirement credits to 72 on the same schedule, would reduce the shortfall by 27%.

Those two types of major proposals still don't entirely eliminate the long-term shortfall. Congress will have to combine them with multiple smaller proposals to reach a satisfactory solution. Other proposals may include increasing the amount of Social Security benefits subject to income tax, subjecting more types of income (such as investment income) to Social Security taxes, and changing the formula for the primary insurance amount.

The sooner Congress acts, the less extreme the changes will have to be. The Social Security Office of the Chief Actuary has been urging legislators to act for decades already. With the problem accelerating this decade, there's hope we'll see serious consideration on the challenge in the near future, but it could be painful for everyone.