For most retirees, Social Security income isn't a luxury. Rather, it represents a financial foundation that many aged beneficiaries would struggle to make do without.

Over the last 24 years, national pollster Gallup has surveyed retirees and found that 80% to 90% of respondents rely on their Social Security payout, in some capacity, to cover their expenses.

Given how important Social Security is to aging workers, you'd think ensuring the financial health of this program would be at or near the top of the list for our elected officials. Unfortunately, lawmakers have been kicking the can for decades, and Social Security's problems -- including the very real possibility of benefit cuts -- may soon come to a head.

While the popular proposal for Social Security's financial shortcomings is to simply tax the wealthy, the grim reality is that this wouldn't resolve the problem.

Image source: Getty Images.

Social Security benefit cuts may be necessary by 2033

Every year since the first retired-worker benefit check was mailed in January 1940, the Social Security Board of Trustees has released a report that intricately details how the program collects income, and tracks where those dollars are spent. For 40 years, every annual Trustees Report has cautioned of a long-term (75-year) funding shortfall.

As of the 2025 Trustees Report, Social Security's long-term unfunded obligation had ballooned to $25.1 trillion -- and it's been growing almost every year.

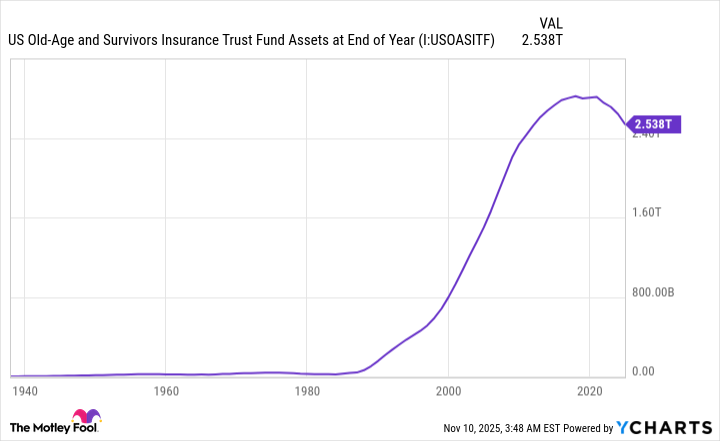

However, the bigger concern is the projection that the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance trust fund (OASI) will completely exhaust its asset reserves by 2033. The OASI is the fund responsible for doling out monthly benefits to retired workers and survivor beneficiaries, and its asset reserves represent the excess income collected since inception. This extra income is invested in special-issue, interest-bearing government bonds, as required by law.

Though Social Security is in no danger of insolvency or bankruptcy, the Trustees Report intimates that sweeping benefit cuts of up to 23% may be necessary by 2033 if the OASI's asset reserves are exhausted.

The blame for Social Security's shortcomings rests primarily with a number of ongoing demographic changes. Some of these you're likely familiar with, such as the retirement of baby boomers and Americans living considerably longer now than when Social Security first began doling out payments in 1940. But not all of these shifts are this visible.

For instance, the U.S. birth rate hit an all-time low in 2024, which threatens to further pressure the worker-to-beneficiary ratio in the coming years.

Additionally, Social Security counts on a steady stream of migrants entering the country to pay into the program via the payroll tax. Net legal migration into the U.S. has declined since the late 1990s.

It's demographic shifts like this -- not myths about "Congress stealing the trust funds" or "undocumented workers receiving traditional Social Security benefits" -- which are causing Social Security's foundation to crumble.

Social Security's OASI is on pace to burn through its asset reserves by 2033. US Old-Age and Survivors Insurance Trust Fund Assets at End of Year data by YCharts.

Taxing the wealthy isn't the cure-all you might think it is

With a better understand of what's wrong with Social Security, the million-dollar question is: How do we fix it?

The most popular solution, by a mile, is to increase payroll taxation on high earners to generate immediate income for Social Security.

In 2025, all earned income (this includes wages and salary, but not investment income) between $0.01 and $176,100 is subject to the 12.4% payroll tax. Meanwhile, earned income above the maximum earnings cap (the $176,100 figure) is exempt from the payroll tax. This tax accounted for more than 91% of the nearly $1.42 trillion the Social Security program collected in 2024.

In case you were wondering, the reason investment income isn't taxed is because your monthly retirement benefit is calculated using your earned income. Since investment income doesn't factor into what you're ultimately paid during retirement, it sidesteps the payroll tax.

Roughly 94% of all workers are paying into Social Security with every dollar they earn (i.e., they'll earn less than the $176,100 earnings cap in 2025). Raising or eliminating the maximum earnings cap would only impact approximately 6% of working Americans, which is why this idea is so popular.

But this isn't the cure-all you might think it is.

Based on an estimate from the Social Security Administration's Office of the Chief Actuary, taxing all earned income would only extend the solvency of the program's trust funds (this means the OASI and Disability Insurance trust fund, combined) by "about 35 years."

Don't get me wrong, 35 years would allow lawmakers to discuss additional options to tackle the program's long-term funding shortfall. It would also firmly kick the asset reserve depletion forecast for the OASI well beyond 2033. But what it doesn't do is come anywhere close to resolving the entirety of the $25.1 trillion 75-year funding deficit.

An argument can also be made that high earners are already paying their fair share. Just as there's a cap to how much earned income is applicable to the payroll tax, there's a hard ceiling to how much beneficiaries can be paid monthly at full retirement age. In 2025, the maximum payout at full retirement age is $4,018 per month.

Image source: Getty Images.

Fixing Social Security will require some tough decisions (and not everyone will be happy)

What makes Social Security so difficult to fix isn't coming up with proposals. Rather, it's the strong likelihood that implementing these changes will adversely impact one or more groups of people, which in turn can cost members of Congress votes in upcoming elections.

To really shore up Social Security for future generations of retirees, workers with disabilities, and survivor beneficiaries, tough choices are going to have to (eventually) be made -- and there's a good chance not everyone will be happy.

Even though the well-to-do are already paying their fair share into Social Security, higher payroll tax revenue is almost certain to be needed to thwart the forecast exhaustion of the OASI's asset reserves. But it might not stop there.

In 1983, a bipartisan Congress passed, and then-President Ronald Reagan signed, the Social Security Amendments of 1983 into law. Among the many changes implemented by this sweeping overhaul of America's leading retirement program was a gradual increase to the payroll tax rate for all workers. Fixing Social Security may require a gradually higher payroll tax rate, regardless of income.

On the other hand, measures will need to be taken to reduce the program's long-term outlays. Although the prospect of reducing benefits in any way is strongly disliked by the public, it may be necessary to ensure the financial stability of Social Security for future generations.

The easiest way to lower future outlays is to gradually raise the full retirement age -- i.e., the age you become eligible to receive 100% of your monthly benefit, as determined by your birth year. The Social Security Amendments of 1983 gradually lifted the full retirement age from 65 to 67, which is where it sits now, over the course of four decades.

Increasing the full retirement age would have no impact on existing retirees and, likely, beneficiaries set to retire in a couple of years. Instead, it would require future generations of retired workers to choose between waiting longer to receive 100% of their monthly benefit, or accepting a steeper permanent monthly payout reduction if claiming early. Either way, this decision reduces the lifetime outlay a retiree would receive.

The one downside worth noting about raising the full retirement age, beyond lower lifetime benefit collection, is that it would take decades before meaningful cost savings would be recognized by Social Security.

Make no mistake about it, Social Security can be made stronger. But it's going to take both political parties and some (likely) unpopular decisions to make it happen.