Social Security's 90th anniversary in 2025 was historic. It marked the first time that the average monthly retired-worker benefit topped $2,000. Further, the 2.8% cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) passed along to the program's more than 70 million traditional beneficiaries in 2026 represents the fifth consecutive year in which benefits have climbed by at least 2.5%. It's been almost three decades since this last happened.

But despite these history-making moments, the foundation of America's leading retirement program is crumbling. Although several factors are responsible for Social Security's shaky financial outlook, it's often our elected officials in Congress who foot the blame.

Image source: Getty Images.

Social Security's estimated 75-year funding shortfall now tops $25 trillion

Each year, the Social Security Board of Trustees publishes a report that delves deeply into the financial outlook for America's top retirement program. It allows anyone to see where Social Security derives its income and tracks where those dollars end up.

However, the most intriguing aspect of the annual Trustees Report is the forward-looking estimate concerning the solvency of Social Security's trust funds.

According to the 2025 Social Security Trustees Report, the program is staring down a $25.1 trillion long-term funding shortfall. In this instance, the "long-term" is defined as the 75 years following the publishing of a report (through 2099).

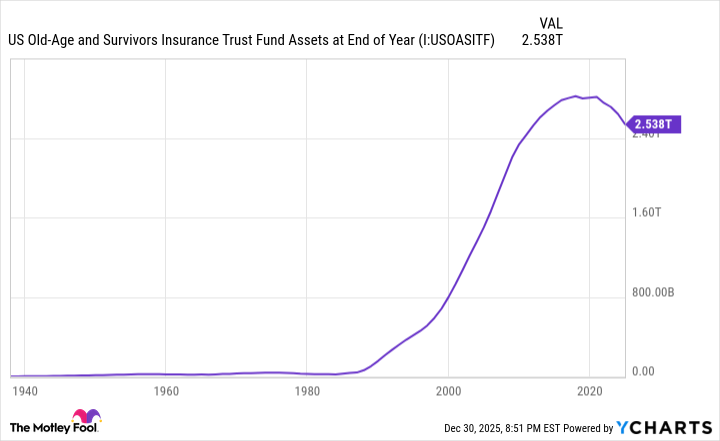

What's arguably even more worrisome is the short-term projections for the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance trust fund (OASI). The OASI is the fund that doles out monthly benefits to retired workers and survivors of deceased workers.

According to the report, the OASI is on pace to exhaust its asset reserves -- the excess income collected, above and beyond outlays, since inception -- by 2033. Although the OASI and Social Security (as a whole) aren't in danger of going bankrupt or halting payouts, sweeping benefit cuts of up to 23% may be necessary for retired workers and survivors of deceased workers in seven years if the OASI's asset reserves are depleted.

Something is clearly amiss with Social Security. Unfortunately, the popular opinion of what's wrong isn't necessarily the correct answer.

Social Security's OASI is projected to exhaust its asset reserves in seven years. US Old-Age and Survivors Insurance Trust Fund Assets at End of Year data by YCharts.

Have our nation's elected officials in Congress stolen from Social Security's trust funds?

If you were to peruse message boards and topics related to Social Security on social media platforms, you're almost certain to come across one or more posts blaming Congress for pilfering Social Security's trust funds and using them to fund wars and other government expenditures. Individuals who believe Congress raided Social Security's trust funds commonly suggest that returning these funds, with interest paid, would resolve the program's funding obligation shortfall.

While posts similar to this tend to garner a lot of interest and likes on social media platforms, they couldn't be more wrong.

When the Social Security Act was signed into law in August 1935, one of its many provisions was that the program's asset reserves be invested in special-issue, interest-bearing government bonds. This means any income collected by the OASI and Disability Insurance trust fund (DI) that isn't outlaid to pay benefits or cover administrative expenses is to be invested in these special-issue bonds, as required by law.

These special-issue government bonds are currently paying interest and are backed by the full faith of the U.S. government. Outside of computer issues and very short-term legislative delays in 1979, the U.S. hasn't defaulted on its outstanding debts in over 200 years. Interest income generated on its asset reserves is one of Social Security's three sources of income.

Additionally, anyone interested can track precisely how much in special-issue bonds and certificates of indebtedness Social Security holds in its investment portfolio at any given time. As of the end of November 2025, $2.555 trillion was invested in the OASI and DI, combined, with an average interest rate of 2.641%.

What this investment portfolio conclusively shows is that the program is adhering to the provisions in the Social Security Act, as required by law, and every cent is fully accounted for in special-issue government bonds. Nothing has been stolen by lawmakers or lost in the shuffle.

Hypothetically, if the U.S. government redeemed this $2.555 trillion and simply returned it to Social Security, the program would lose out on more than $60 billion in estimated annual interest income. In other words, if the federal government doesn't borrow this excess income, Social Security's financial outlook would be materially worse.

Image source: Getty Images.

Here's what's really to blame for Social Security's financial woes

With the claim that Congress stole from Social Security clearly debunked, attention can be turned to the actual factors responsible for the program's financial woes -- ongoing demographic changes.

Some demographic shifts are well known or have been ongoing for quite some time. For instance, baby boomers have been leaving the labor force for years, which is weighing on the worker-to-beneficiary ratio. There simply aren't enough new workers entering the labor force to offset those retiring.

Life expectancy is also notably longer now than when Social Security's first retired-worker check was mailed in January 1940. To be somewhat blunt, Social Security was never designed to support beneficiaries for multiple decades.

However, an assortment of under-the-radar demographic shifts is adversely affecting America's leading retirement program, as well.

For example, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that the U.S. fertility rate hit an all-time low in 2024. For a generation to have enough children to replace itself, a fertility rate of 2.1 kids per woman is needed. In 2024, the U.S. fertility rate clocked in at less than 1.6. This is expected to negatively impact the worker-to-beneficiary ratio in the coming decade.

Net legal immigration into the U.S. has also declined since the late 1990s. Social Security relies on a steady stream of legal migrants entering the country. Since immigrants tend to be younger, they'll spend decades in the workforce contributing via the 12.4% payroll tax on wages and salaries. Fewer net legal migrants mean less in the way of payroll tax collection.

Social Security faces an income inequality problem, too. In 1983, approximately 90% of wages and salaries were subject to the payroll tax. But as of 2024, only 83% of earnings in covered employment were taxable. Put simply, more earned income is escaping the payroll tax over time.

Lastly, Congress deserves its fair share of the blame -- but not for theft. The finger can be pointed at elected officials for sweeping these issues under the rug. The longer lawmakers wait to fix Social Security, the costlier the solution will be for workers and the program's traditional beneficiaries.

Social Security has numerous issues to contend with, but congressional theft isn't one of them.