It’s a simple difference, but a big distinction: There are tax brackets, and then there’s your tax bill.

The United States has a progressive federal income tax system that's based on brackets, also known as marginal rates. Your marginal rate -- your top tax bracket -- will likely be considerably more than your effective rate. Here, we’ll explain the difference and the history of marginal and effective tax rates and provide an example of how it works.

What is an effective tax rate?

There are two common ways of measuring a federal income tax rate. The effective tax rate is the percentage of your taxable income that you actually pay in taxes. Marginal tax rate, also known as a bracket, essentially tells you the tax rate you'll pay on the last dollar you earn.

If you earn a million dollars, chances are good that you’re in the highest bracket (currently 37%). But that doesn't mean your effective tax rate is 37% if you're a seven-figure earner.

Marginal tax rate applies only to the portion of your income that falls within your highest tax bracket -- not your entire income. So, even if your taxable income falls into the highest bracket, not all your income is taxed at that level. Instead, the tax rates climb progressively as your income expands into the next bracket. Even if your marginal tax rate is 37%, your effective tax rate will be lower because not all of your income will be taxed at a 37% rate.

History of tax rates

Reintroduced in 1913, the federal income tax was designed to be progressive. That means people with higher incomes would pay higher tax rates.

When it was launched, for example, an average tax rate of 1% was applied to the poorest households; income above $500,000 (roughly $16 million in 2025 dollars) was taxed at a rate of 7%. Given that the average per capita income was $333, only 0.8% of Americans paid any federal income tax at all.

The top tax rate fluctuated over the next few decades. It soared to 77% to pay for World War I before falling to as little as 25% on the eve of the Great Depression. It rose sharply during World War II, climbing to a record of 94% in 1944-45 and staying in the 90% range through 1963.

Marginal rates plummeted to 28% from 1988 until 2000 before creeping back up. Though marginal tax rates climbed as high as 39.6%, since 2018, the highest tax bracket has been 37%.

An analysis by Fidelity, however, found much less movement in the average effective tax rate for U.S. households. In 2001, the typical American household handed over 14.47% of its taxable income to the IRS; by 2021, the figure had climbed to 14.9%, the highest rate in two decades. Over the 20-year period, it ranged from a low of 11.39% in the midst of the Great Recession in 2009 to the 2021 high.

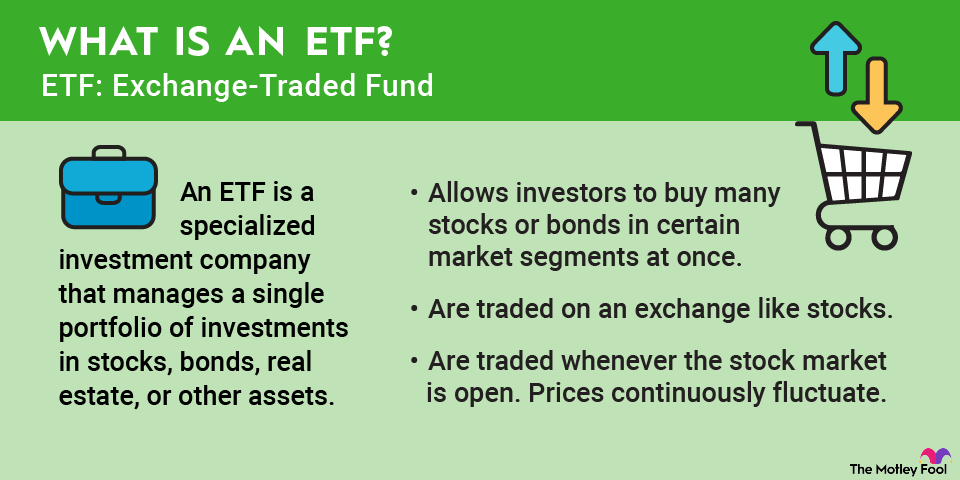

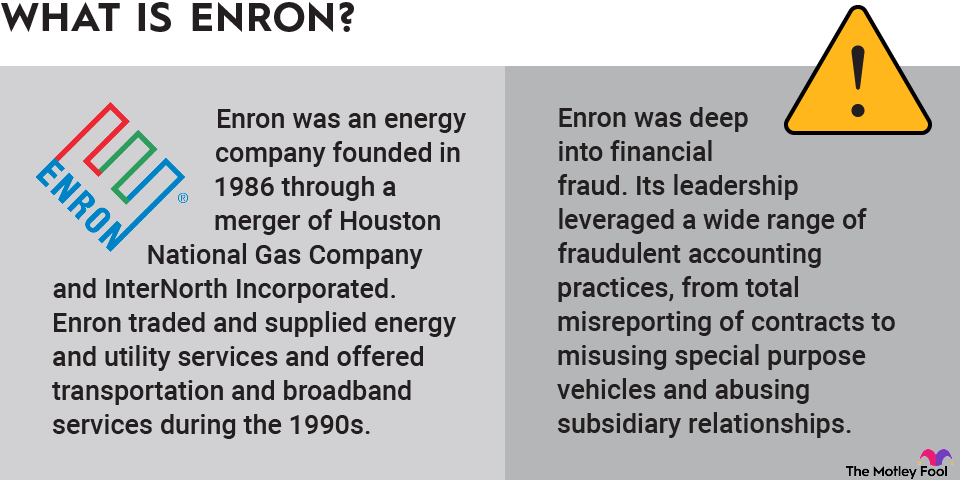

Related investing topics

Calculating effective tax rates

Let’s say you and a spouse had a taxable income of $100,000, placing you into a 22% bracket. That doesn’t mean your federal tax bill would amount to $11,828. Instead, your marginal rate would be calculated like this:

10% of your first $23,850 = $2,385

12% of your earnings between $23,851 and $96,950 = (12% of $73,099, or $8,772)

22% of your earnings between $96,950 and $100,000 = (22% of $3,050, or $671)

Total tax bill = $11,828

Tax Rate | For Single Filers | For Married Individuals Filing Joint Returns | For Heads of Households |

|---|---|---|---|

10% | $0 to $11,925 | $0 to $23,850 | $0 to $17,000 |

12% | $11,925 to $48,475 | $23,850 to $96,950 | $17,000 to $64,850 |

22% | $48,475 to $103,350 | $96,950 to $206,700 | $64,850 to $103,350 |

24% | $103,350 to $197,300 | $206,700 to $394,600 | $103,350 to $197,300 |

32% | $197,300 to $250,525 | $394,600 to $501,050 | $197,300 to $250,500 |

35% | $250,525 to $626,350 | $501,050 to $751,600 | $250,500 to $626,350 |

37% | $626,350 or more | $751,600 or more | $626,350 or more |

To calculate your effective tax rate, you'd divide your total tax bill ($11,828) by your taxable income ($100,000) for a figure of about 11.8% -- significantly lower than your marginal tax rate of 22%.