U.S. stocks skyrocketed in the decade following the Great Recession. The S&P 500 bottomed out on March 9, 2009. By the end of 2019, it had surged 378% from that low. Including reinvested dividends, the index had jumped nearly 500%.

At first, it seemed like the COVID-19 pandemic would end that remarkable streak of gains. At one point in late March, the stock market had plunged by 30% from where it began 2020. Since then, stocks have rallied yet again. The S&P 500 is now up about 15% year to date.

S&P 500 year-to-date performance and total return, data by YCharts.

That solid increase pales in comparison to the massive gains posted by some high-growth companies. For example, Roku (ROKU 4.46%) stock has surged 146% year to date. The Trade Desk (TTD 5.06%) shares have jumped 263%. Big gains like these have made many investors greedy for more. More than three decades ago, Warren Buffett cautioned investors to avoid getting swept along by the herd during such episodes of mass greed.

Wise words from the Oracle of Omaha

In his 1986 letter to shareholders, Buffett observed that "occasional outbreaks of ... fear and greed, will forever occur in the investment community." The legendary investor continued:

[T]he market aberrations produced by [fear and greed] will be equally unpredictable, both as to duration and degree. Therefore, we never try to anticipate the arrival or departure of either disease. Our goal is more modest: we simply attempt to be fearful when others are greedy and to be greedy only when others are fearful."

Buffett returned to this theme periodically in subsequent years. His key insight remained the same, though. There's no way to know when greed-driven rallies or fear-driven market declines will end.

The best thing long-term investors can do when the market seems to be caught in a speculative bubble is to act extremely cautiously -- which might mean selling overpriced shares of great companies. By contrast, the time to aggressively load up on shares of great businesses is when other investors are selling them in a panic.

Great companies aren't always great stocks

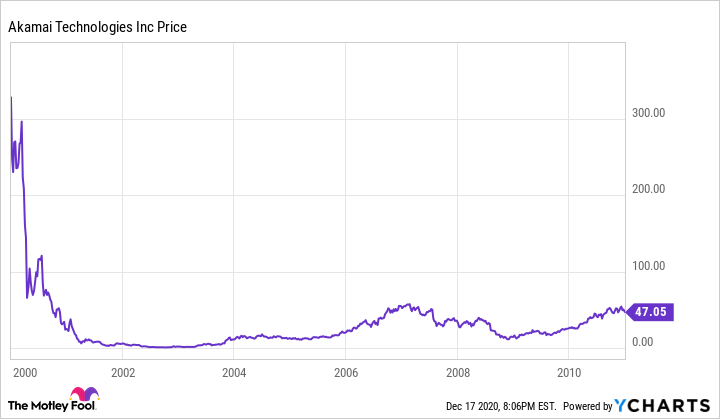

The history of Akamai (AKAM 1.03%) highlights the risk of investing at elevated valuations. Akamai created the first content delivery network (CDN) in the late 1990s. CDNs speed up websites by storing information in multiple locations around the world so that content is closer to end users.

Akamai started operations in 1999. In 2000, its first full year of generating revenue, it rang up $90 million of sales. Despite a brief setback in 2002, after the bursting of the tech bubble and 9/11, revenue tripled to $285 million by 2005. Revenue more than tripled again over the next five years, reaching $1.02 billion in 2010. Meanwhile, Akamai went from losing money and burning cash in 2000 to achieving a stellar 25% operating margin a decade later.

Clearly, Akamai is a great company. It identified an unmet need, created a substantial business built around serving that need, and earned high margins while doing so.

It didn't work out for shareholders, though. Akamai stock plunged 86% between the beginning of 2000 and the end of 2010. Even today, the stock is down 68% from where it ended 1999. Akamai's market cap of roughly $30 billion entering 2000 was way too high, notwithstanding the strong revenue and earnings growth it delivered over the following decade.

Akamai 2000-2010 stock performance, data by YCharts.

Greed may be driving a repeat

Today, market euphoria has again driven shares of many great companies to levels that don't make sense. Roku and The Trade Desk are good examples.

Rapid consumer adoption of streaming video is driving strong growth for both Roku and The Trade Desk. Roku sells its widely used streaming devices and provides software for connected TVs, but generates the bulk of its profit from selling ads that are shown to Roku users on ad-supported services. The Trade Desk helps advertisers optimize their spending via programmatic ad campaigns. While the company supports everything from display ads to audio ads to social ads, connected TV video ads have been a huge growth driver recently.

Both companies are positioned to benefit as more consumers cut the cord and spend more time streaming. Analysts expect The Trade Desk to grow revenue 22% this year (despite a big dip in the second quarter) and 34% in 2021. Roku is growing even faster -- analysts expect revenue to surge 53% in 2020 and another 38% in 2021.

Image source: Getty Images.

Yet while all forms of streaming entertainment are growing rapidly now, ad-free services like Netflix seem destined to be the biggest winners. That will ultimately constrain the long-term earnings potential of Roku and The Trade Desk. Both companies still have plenty of growth ahead of them and merit high valuations -- perhaps as much as 15 to 20 times sales. However, The Trade Desk trades for about 55 times its projected 2020 revenue. Roku is cheaper, at 24 times projected 2020 revenue. But excluding its device business -- which is essentially a loss leader -- it trades for around 35 times revenue.

Buying and holding shares of great businesses is the surest path to investing success. However, Buffett's lessons about greed and fear remind us that the best businesses can be bad investments if the price tag is too high. That seems to be the case for The Trade Desk and Roku (and a good many other companies) today.

Even if they grew revenue close to tenfold by 2030, their share prices would likely underperform for long-term investors -- as early Akamai investors learned the hard way. In the current market, investors are better served being fearful rather than greedy. Sooner or later, another market crash will come, creating new opportunities for patient investors.