Investing in bonds can be an excellent way to earn some return on your capital while reducing the risk of losses. This is especially valuable as you get close to a financial goal because stock market volatility can result in big -- and fast -- capital losses.

A corporate bond is a debt obligation a business issues to raise money. Corporate bond buyers are lending money to the company, which is legally obligated to pay interest as agreed upon to bondholders.

When a corporate bond matures (i.e., reaches the end of the term), the company repays the bondholder. Corporate bonds usually have higher yields than Treasury bonds issued by the federal government or municipal bonds issued by state and local governments.

How do corporate bonds work?

A corporate bond is a loan made to a company for a predetermined period. In return, the company agrees to pay a predetermined interest yield (typically twice per year) and then repay the face value of the bond once it matures.

Let's use a typical fixed-rate bond as an example. If you invest $1,000 in a 10-year bond paying 3% fixed interest, the company will pay $30 per year and return your $1,000 in a decade. While fixed-rate bonds are the most common, there are others to consider, including:

- Floating-rate bonds: These bonds have variable interest rates that change based on benchmarks, such as the U.S. Treasury rate. They are usually issued by companies considered below investment grade (i.e., those considered junk bonds).

- Zero-coupon bonds: These don't come with interest payments. Instead, you pay below face value (the amount the issuer promises to repay) and receive full value at maturity.

- Convertible bonds: These bonds give companies the flexibility to pay investors with common stock instead of cash when a bond matures.

How to buy corporate bonds

In general, there are three ways to buy corporate bonds:

- New issue

- Secondary market

- Bond funds

Companies looking to raise cash offer new issue bonds through an intermediary broker-dealer. You pay face value, and the company receives the proceeds, minus any fees retained by broker-dealers for their services.

The secondary market is where you can buy already-issued bonds from investors who own them and are looking to sell them before maturity. The price may be higher or lower than face value depending on interest rates (to keep the yield competitive with yields paid by new issues) and the financial condition of the issuing company.

For instance, bonds issued by a company that may be unable to meet its financial obligations often trade at a discount to face value on the secondary market. This is to compensate buyers for taking on the risk that a company won't be able to pay its obligations.

A bond fund lets you invest in a broad group of bonds, and a number of bond funds invest exclusively in corporate bonds. Individual bonds typically require a minimum $1,000 investment, which could make it difficult for many people to build a diversified bond portfolio.

If you're working with smaller amounts of money, a bond fund could be ideal since the minimum investment is the price of a single share of a bond exchange-traded fund (ETF) or mutual fund. Bond funds do come at a price, though.

The fund manager has expenses to cover and wants to earn a profit as well. Make sure to understand the fees you'll pay -- measured as an expense ratio -- before investing in a bond fund.

How to make money from corporate bonds

Investing in corporate bonds is generally part of a strategy to protect your capital and earn a profit from the interest paid as part of a diversified portfolio of stocks and bonds. You can also make money by investing in bonds trading at a discount to face value (also called par value).

This can occur for a couple of reasons. One reason is a change in the interest rate environment. If interest rates rise, investors can earn more with new issues, so existing bonds will be discounted to compete with new issues.

A bond may also be discounted if a company is at risk of not meeting its debt obligations or may be forced to issue stock to pay off convertible bonds. In these instances, bondholders are often willing to sell below face value -- how much the bond investments cost at issuance -- to reduce the risk of higher possible losses.

There's certainly more risk with bonds in such situations since these companies could default on their debts, resulting in losses for their bondholders.

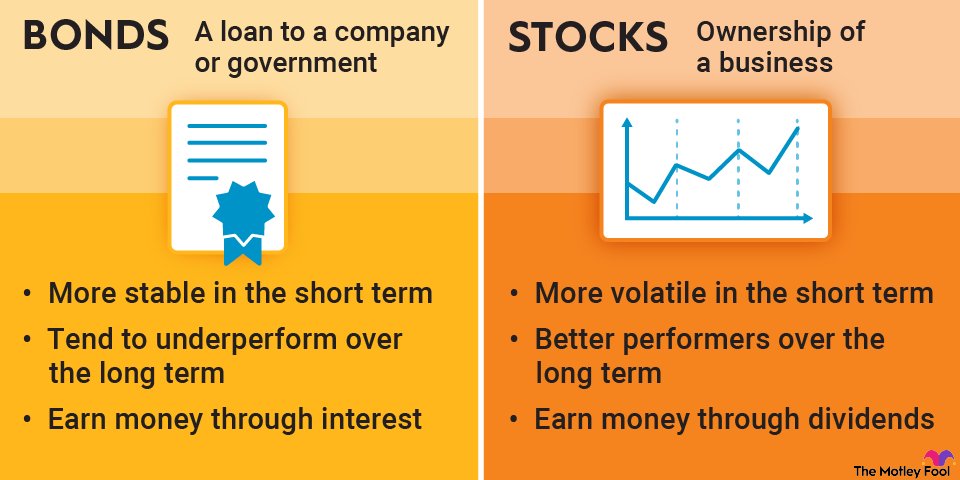

Corporate bonds vs. stocks

Stocks represent direct ownership in a business, while bonds are loans with a predetermined rate of return. This is why, even for a strong and profitable company, the value of its bonds will hold stable even if the stock price changes substantially. You usually know exactly what you're getting with a bond.

A company's stock price, however, can fluctuate substantially and is often based on projections of what people think the company could earn in the future. As a result, stock prices can be volatile, while corporate bonds tend to hold their value. You trade the potential upside of stocks for the predictability of bonds.

Pros and cons of corporate bonds

As noted, the biggest benefit of corporate bonds is stability. Even the best companies' stocks can crash with the market, and this volatility can lead to big losses if you need to sell at a specific time. But bonds tend to hold up across every economic environment as long as the issuing company remains in good shape.

The drawback is that this stability comes at the expense of lower long-term returns. Corporate bonds are ideal stores of value for wealth you'll depend on in the next five years or less. Over longer periods, bonds don't match the wealth-building power of stock ownership.

Don't simply buy bonds with the highest yields based on your time frame. Make sure you diversify for risk factors.

For instance, buying bonds only from companies in the same industry or with exposure to the same risks could result in a riskier bond portfolio, particularly if you also have a lot of stock exposure to those same companies. Think through each bond purchase and how it fits into your portfolio.

Are corporate bonds right for you?

Are you only a few years from a financial goal? If so, it may be time to start shifting some of your assets away from the volatility of stocks and adding more corporate bonds to your holdings.

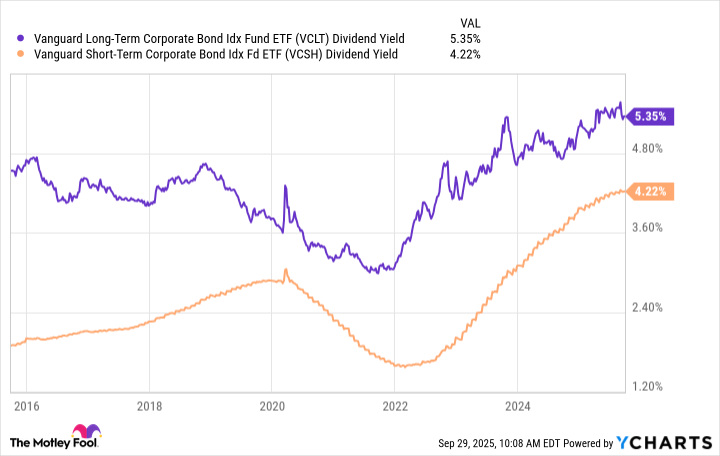

Just remember that, as the chart above shows, corporate bonds have historically underperformed stocks over the long term. Too much exposure to bonds too early can hamper your returns, leaving you with less wealth than you had planned.

Related investing topics

There's also a psychological side to consider. Many investors struggle with holding stocks through a market downturn.

If owning more bonds reduces the likelihood that you'll cash out of stocks in a market crash (or pile into stocks during a period of extreme exuberance), owning more bonds than is typically recommended for your age and stage of life could be the right move for you. In that case, the higher yields of corporate bonds vs. Treasury bonds can help offset the "lost" returns from not owning more stocks.