Simple returns

There are two ways to express investment returns over time: simple and compound. A simple return (or simple interest) is a rate of return based on the principal (i.e., the original investment amount) year after year.

This is often used in the context of fixed-income (bond) investments. For example, if a bond costs $1,000 and yields 5%, that is a form of simple return -- in other words, 5% of the original cost, or $50, will be paid to the bondholder every year until maturity.

Compound returns

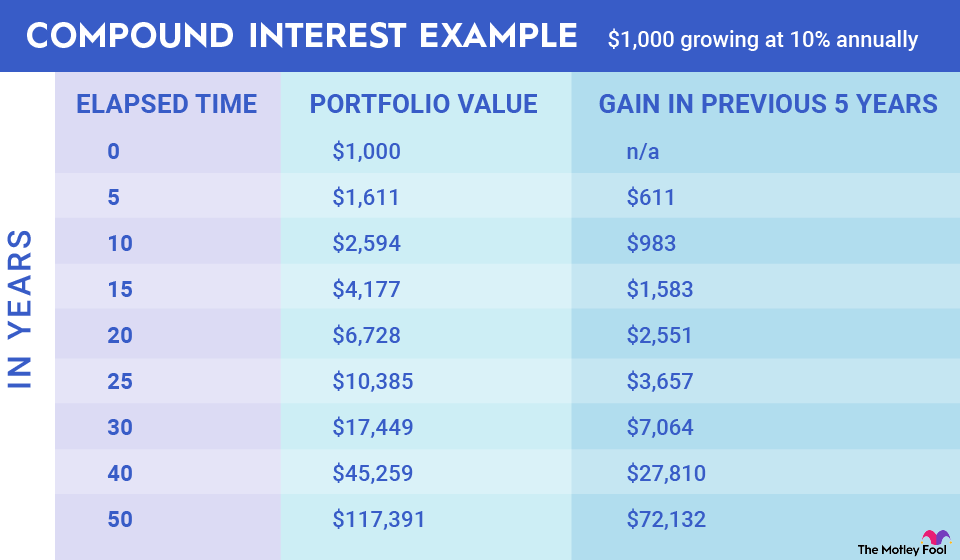

A compound return (or compound interest) is a return that is paid on the principal and any accumulated returns that have already been paid. Annualized total return is a form of compound return.

As a simplified example to illustrate compound returns, consider an investment that generates a 10% annualized total return. If you invest $1,000, you can expect to have $1,100 by the end of the first year. For the second year, however, the 10% would be added to the $1,100, not the original $1,000. So, you'd end up with $1,210 at the end of the second year.

Compounding frequency

The method most often used to calculate total returns is annual compounding. That's what the formula I will discuss in the next section will do.

However, other compounding intervals are possible when computing returns and interest charges in finance. For example, your bank probably compounds your interest daily or monthly on your savings account. Other intervals, like quarterly, weekly, or semiannual compounding, are also possible.

To give you just an idea of how this works, a $1,000 investment that generates 10% total returns compounded semiannually would be worth $1,050 after six months. After another six months, a 5% (half of the annual return) gain would be added, which would make it $1,102.50.

Dividend reinvestment/DRIP

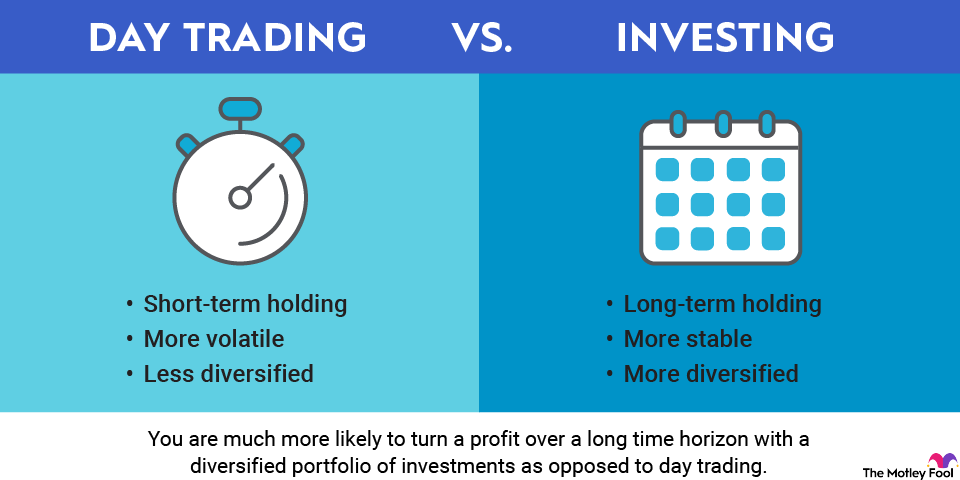

To maximize the total returns of a long-term investment, dividend reinvestment is an essential step. This means that when your stocks pay you dividends, you use those dividend payments to buy additional shares of the same stock.

With most brokers, you can enroll your stocks in a dividend reinvestment plan (DRIP) that will do this automatically and without any additional trading commissions. If you're a long-term investor, enrolling in a DRIP can help you maximize your total returns, and it can make more of a difference than you might think over long periods.

Internal rate of return (IRR)

Internal rate of return (IRR) is similar in concept to total return. However, it involves a more complicated calculation.

Aside from its complexity, the biggest difference between IRR and total return is that IRR is a forward-looking metric that incorporates things like projected dividends or distributions, future profitability, and more. This is more commonly used when talking about real estate investments, but it can also be applied to stocks when trying to project long-term returns from different prospective investments.

Expected total return

Expected total return is the same calculation as total return but using future assumptions instead of actual investment results. For example, if you predict that a stock trading for $30 will rise to $33 over the next year while paying $2 in dividends, your expected total return is $5 per share or 16.7%.

Obviously, nobody has a crystal ball that can predict stock performance, and an investment's past performance doesn't guarantee its future results. That said, projections can still be a valuable tool when analyzing opportunities, so using the information you have to calculate the expected total return can help you get an idea of the future potential of certain investment opportunities.

Risk-adjusted return

This uses the risk-free rate of return and investment volatility to account for an investment's risk level when calculating returns. A basic investment goal is to maximize the amount of return produced by investments relative to the total risk. In other words, a lower return from a low-risk investment can be a better risk-adjusted return than a superior return produced by a higher-risk investment.

One popular way to assess risk-adjusted returns is with a metric called the Sharpe ratio. This not-too-complicated metric subtracts the risk-free rate of return from an investment's actual return and then divides it by the standard deviation (volatility) of that return.

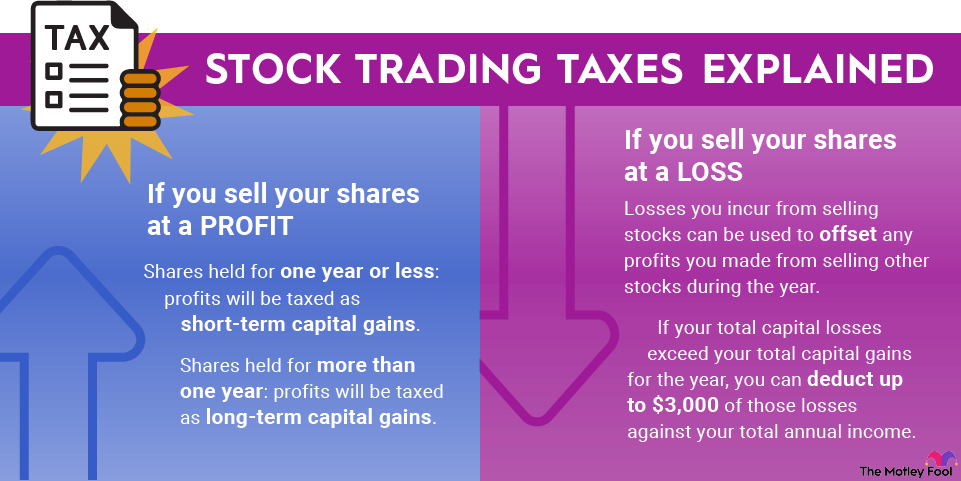

Unrealized versus realized capital gains

An unrealized capital gain refers to a stock or other investment that has increased in value since you bought it but that you still own. In other words, if you paid $5,000 for a stock investment that is now worth $6,000, you can't spend that $1,000 of profit until you sell. Once you sell an appreciated investment, it is then referred to as a realized capital gain. This is an important concept in the context of total returns.

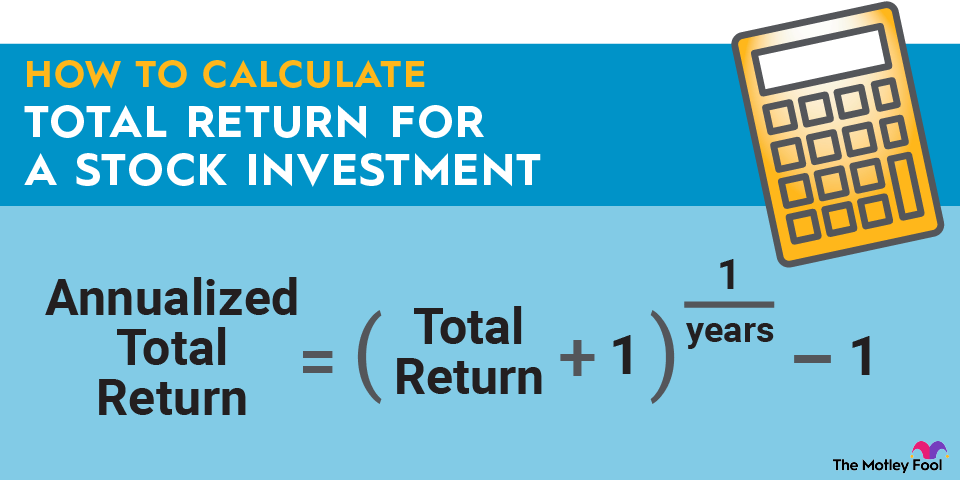

How to calculate total return for a stock investment

Now, we'll go through the process of calculating total returns. There are a few ways to calculate total return depending on the exact form of the metric you're looking for, but the good news is that none of them are particularly complex.

To determine an investment's overall total return, follow these steps:

- First, determine how much capital gains it has produced since you bought it. For instance, if you paid $50 for a stock that's now trading for $60, your capital gain is $10 per share.

- Second, you need to add up the dividends and other distributions the investment has paid over your entire holding period. Adding this figure to your capital gains will give you the investment's total return in dollars.

- Third, to express total return as a percentage, which is generally more useful, simply take the dollar amount of total return you calculated, divide it by the price you paid for the investment, and multiply the result by 100.

- Finally, to annualize the total return, you'll need a bit more complicated math. Take the percentage total return you found in the previous step (written as a decimal) and add 1. Then, raise this to the power of 1 divided by the number of years you held the investment. Finally, subtract 1. In mathematical form, this looks like:

The bottom line on total return

Total return is a great metric to add to your investment knowledge. Some investments are designed to produce a great deal of capital appreciation, while others are intended to produce income. Total return combines these two types of investment performance into a single metric.

Knowing how to calculate and apply total return can help you evaluate the overall performance of different stocks, compare different potential investments, and understand the value of dividend reinvestment, to name just a few things.