It is common knowledge that the goal of investing is to buy low and sell high. The technical term for this is capital appreciation, and it's an important concept for investors to know since it can have tax implications and is only one of the two ways investments can make money.

Understanding capital appreciation

Capital appreciation refers to the change in an investment’s market price over time, relative to the price paid, or cost basis. It can be used in reference to liquid investments like stocks, or illiquid investments like real estate. It can also refer to the price of precious metals like gold, assets such as collectibles, or pretty much anything else that has a quantifiable market value.

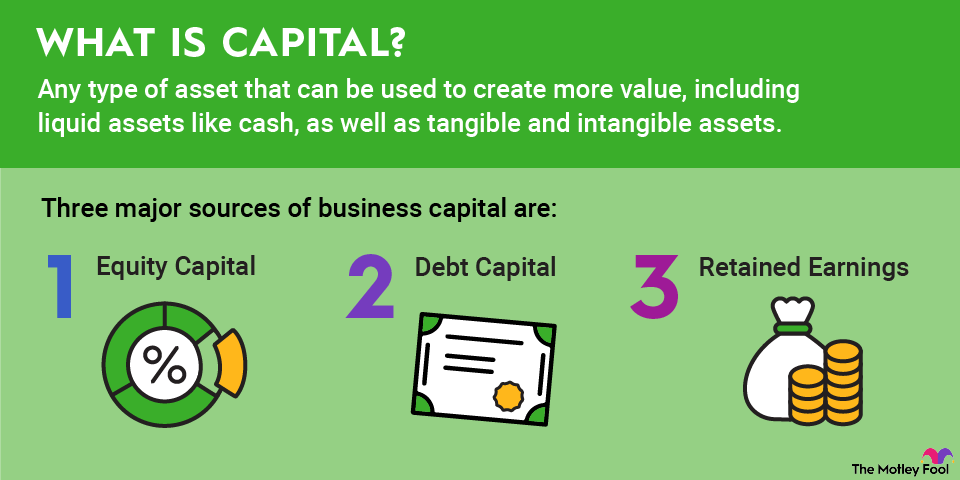

Capital

For example, if you paid $40 for a stock and it is now worth $70, you would have $30 in capital appreciation.

Capital appreciation can be expressed on a per-share basis or for your total investment, and it also can use an investment’s market price, or the selling price.

Capital appreciation vs. total returns

Capital appreciation is one of two main ways investors (hopefully) make money. As mentioned, capital appreciation occurs when an investment is worth more than you paid for it.

In addition to capital appreciation, investors can also get income from their investments. When it comes to the stock market, income is typically received in the form of dividends. Income can also come in the form of interest, royalties, or other types of payments.

Many investments don’t pay dividends or other distributions to investors, while others are more focused on generating income than producing capital appreciation. For this reason, simply looking at stock price performance over time isn’t the best way to compare the stocks you own. So, investors often look at the total return of an investment to make a fair comparison between investments with different focuses. A total return is the combination of dividends and capital appreciation. For a simplified example, if a stock rises by 6% in a year and pays a 4% dividend yield, it has a total return of 10%.

Capital appreciation vs. capital gains

Capital appreciation is typically used to refer to the gains on an investment that you still own, as opposed to investments you’ve sold and collected your profits. In other words, capital appreciation is often associated with unrealized gains. However, capital appreciation can be used to refer to an entire portfolio, which would include both realized and unrealized investment gains.

Once you sell an appreciated asset, it becomes a capital gain, which is important for tax purposes. Under the U.S. tax code, you only have to pay taxes on realized investment processes, not unrealized gains. Regardless of how much your investments have grown in value; you typically won’t have any tax implications until you decide to sell.

It’s also important to point out that it’s entirely possible for an investment to produce negative capital appreciation if its market value declines. If you sell an investment for less than your cost basis, it results in a capital loss. If it’s an investment you still own, it would be referred to as an unrealized loss.

Example of capital appreciation

Let’s say that you own a stock that you purchased for $50 per share three years ago. It currently trades for $75 per share and has paid a total of $10 in dividends since you bought it.

You would have $25 in capital appreciation on the stock, which would correspond to a 50% unrealized gain. You would also have received a 20% overall dividend yield on your cost. Combining these two figures would result in a 70% total return. Many investors like to express returns on an annualized basis to compare the performance of investments with different holding periods, and since you’ve owned the stock for three years, this corresponds to a 19.3% annualized total return.