Since January 1940, Social Security has been providing a financial foundation for aging workers who could no longer do so for themselves. According to almost a quarter century of annual surveys from national pollster Gallup, between 80% and 90% of retirees rely on their monthly payout to cover at least some portion of their expenses.

Considering how important Social Security is to the financial well-being of our nation's retired workers, you'd think lawmakers would prioritize its financial health. But over the last four decades, the foundation of America's leading social program has been crumbling.

Image source: Getty Images.

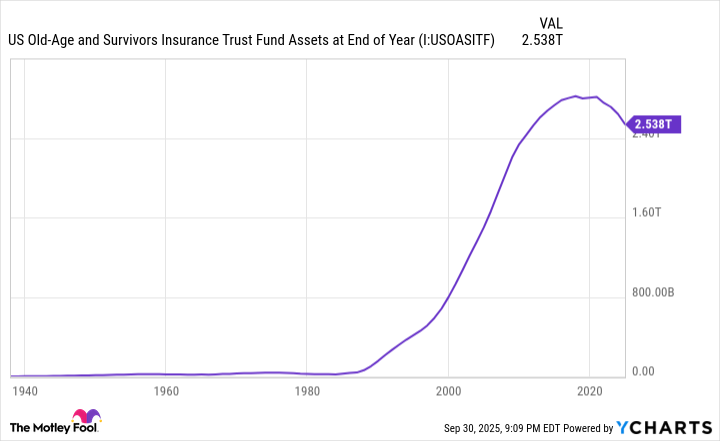

By one estimate, the Old-Age and Survivors Insurance trust fund (OASI), which is responsible for doling out benefits to retired workers and survivors of deceased workers, is expected to exhaust its asset reserves seven years from now. This timeline has been sped up by the signing of the "Big, Beautiful Bill" into law by President Donald Trump.

While Social Security is in absolutely no danger of going bankrupt, becoming insolvent, or halting benefits, maintaining the existing payout schedule, inclusive of annual cost-of-living adjustments, is very much at risk beyond the fourth quarter of 2032.

Strengthening Social Security will require tough and potentially unpopular decisions, which is something the program's newest Commissioner, Frank Bisignano, seems to recognize.

What's really wrong with Social Security?

Peruse social media and you'll find no shortage of claims as to why Social Security is struggling, ranging from Congress stealing from the program's trust funds to undocumented migrants receiving traditional benefits. But neither of these claims have any substance or facts to back them up.

According to the 2025 Social Security Board of Trustees Report, the program is staring down a $25.1 trillion funding shortfall over the next 75 years, as well as an expected depletion of the OASI's asset reserves. If this excess income since inception dwindles to $0, sweeping benefit cuts of up to 23% may be necessary to avoid the need for any further reductions until 2099.

Sweeping benefit cuts will be necessary if the OASI's asset reserves run dry. US Old-Age and Survivors Insurance Trust Fund Assets at End of Year data by YCharts.

The blame for Social Security's worsening financial outlook predominantly rests with five ongoing demographic shifts:

- Baby boomers are retiring from the labor force and weighing down the worker-to-beneficiary ratio.

- Beneficiaries are living considerably longer now than they were when payouts first began in 1940. Social Security wasn't designed to dole out benefits for multiple decades.

- Net legal migration into the U.S. has shrunk since the late 1990s. Social Security relies on younger migrants legally entering the country and contributing via the payroll tax on earned income.

- The U.S. birth rate hit an all-time low in 2024, which will further depress the worker-to-beneficiary ratio in the coming decade.

- Wages and salaries for high earners have grown at a faster pace than the earnings tax cap associated with the payroll tax, leading to more earned income escaping this tax. All earned income from $0.01 to $176,100 is subject to the payroll tax in 2025, with earnings above $176,100 (the earnings tax cap) exempted.

Congress also deserves some blame -- but not for the myth of stealing money. Rather, it's the inaction of lawmakers and/or unwillingness to find common ground that's led to this problem being kicked down the road year after year.

"Everything's being considered"

New Social Security Administration (SSA) Commissioner Frank Bisignano is keenly aware of the ramifications of doing nothing for the program's more than 70 million traditional beneficiaries (retired workers, workers with disabilities, and survivors of deceased workers). It's why he shared the following must-see statements on Fox Business's Mornings with Maria:

Fox Host: "Would you consider raising the retirement age?"

-- More Perfect Union (@MorePerfectUS) September 19, 2025

Trump's Social Security Administration Commissioner: "I think everything is being considered, yeah." pic.twitter.com/kdyVlyN7pX

The unmistakable takeaway of Bisignano's statements was his declaration that "everything's being considered," in relation to host Maria Bartiromo's question about raising Social Security's full retirement age. A worker's full retirement age represents the age where the person becomes eligible to receive 100% of the monthly benefit. For workers born in or after 1960, their full retirement age is 67.

It should be noted that Bisignano clarified his statement mere days after his interview to note that raising the full retirement age isn't on the table. President Trump has previously proclaimed that his administration would protect Social Security benefits, and raising the full retirement age would work against that claim.

With increasing the full retirement age off the table, in Bisignano's view, this leaves a few key options to strengthen Social Security.

One possibility is increasing or completely eliminating the taxable earnings cap. Placing the 12.4% payroll tax on wages and salary (but not investment income) above $176,100 would generate plenty of additional income for the program. Reinstating the payroll tax on the top 1% of earners is an idea that both former President Joe Biden and Vice President/Democratic Presidential nominee Kamala Harris floated to strengthen Social Security.

Since raising or eliminating the payroll tax would affect only 1% to 6% of workers (i.e., most workers are paying into Social Security via the payroll tax on every dollar they earn), it's a proposal with a lot of support.

Another idea that's been floated from time to time is means-testing benefits. This would involve phasing out or eliminating payouts to individuals earn who too much money.

While these popular ideas would improve Social Security from a financial standpoint, they don't come particularly close to resolving the program's financial shortcomings.

Image source: Getty Images.

Despite its unpopularity, raising the full retirement age should be on the table

Social Security is the perfect example of what's popular not always being the best choice. Statistically, increasing taxation on high earners, or all working Americans, makes sense. An immediate boost in income will be needed to offset the expected exhaustion of the OASI's asset reserves in the coming years.

But analyses have shown that taxing high earners, or even all earned income for that matter, doesn't resolve Social Security's projected 75-year funding shortfall. A 2021 study from the SSA's Office of the Chief Actuary examined what would happen if all earned income was subject to the payroll tax:

If all earnings were subject to the payroll tax, but the current-law base were retained for benefit calculations, the Social Security trust funds [OASI and Disability Insurance trust fund, combined] would remain solvent for about 35 years.

Don't get me wrong: 35 years buys lawmakers time to come up with additional solutions. However, the unpleasant point is that a unilateral approach solely focused on "taxing the rich" doesn't, by itself, fix Social Security. It stops the bleeding for a few decades, but puts Social Security on course for benefit cuts in three to four decades.

Although raising the full retirement age is a solution that's broadly disliked, it should absolutely be on the table as a tool to strengthen Social Security.

Raising the full retirement age wouldn't impact current retirees receiving benefits, nor retired workers set to receive benefits in the coming years. Rather, it would be enacted gradually and require workers expected to retire decades from now to make a choice: wait longer to receive 100% of their monthly benefit, or collect early and accept a potentially larger permanent reduction to their payout. Either way, gradually increasing the full retirement age would lower lifetime outlays for Social Security.

The value of putting this solution on the table is that it helps cover more bases. Expanding payroll tax collection on high earners provides the immediate income boost to offset the projected OASI asset reserve depletion. Meanwhile, gradually increasing the full retirement age reduces outlays decades from now amid a long-term increase in U.S. life expectancy.

While gradually raising the full retirement age, in combination with exposing more earned income the payroll tax, might not be enough to completely close the projected $25.1 trillion unfunded obligation over the next 75 years, this combined approach would be considerably more effective than unilateral attempts to simply do what's popular.