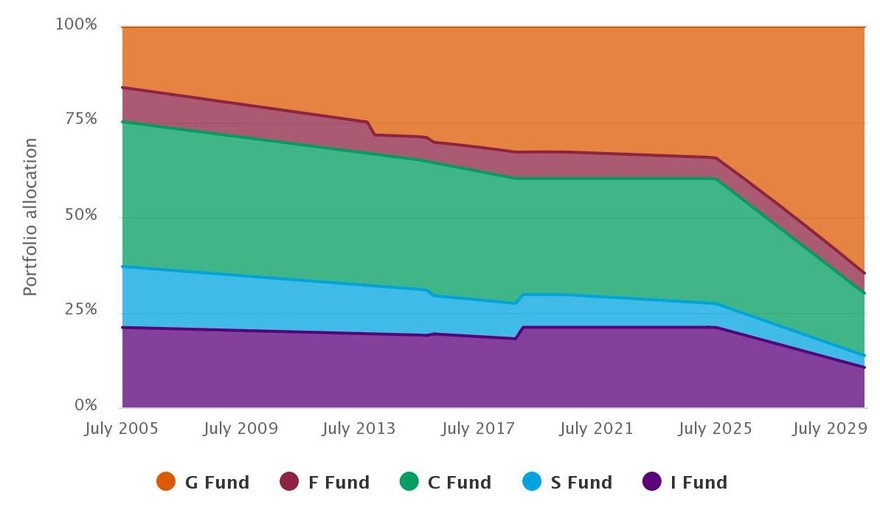

As you can see, when someone is about 25 years from retirement, the lifecycle funds invest 75% of their assets in stocks. The fund gradually shifts the asset allocation from stocks to bonds but then rapidly shifts to bonds about five years from the target date.

Those final five years could be crucial to meeting a retirement goal, and a big downturn in stocks could be devastating, so bonds are an appropriate means of preserving capital near retirement. As the fund moves past the retirement date, it'll eventually start modestly increasing exposure to stocks again to maximize the potential lifetime income from the portfolio.

Should you buy a lifecycle fund?

The key advantage to a lifecycle fund is the convenience of having a set-it-and-forget-it retirement plan, but investors should be aware of their shortcomings. Relatively high fees, compared to simple index funds, are one factor that can limit returns for lifecycle funds. Be sure to check the fees you're paying for convenience and weigh the cost against the benefits.

Although they may do an adequate job of rebalancing your investments as you age, keep in mind that no two lifecycle funds ever follow the exact same path. Be sure to check the prospectuses of any funds you're considering to determine which fits your retirement strategy best.

Finally, lifecycle funds assume that your only investment and only source of retirement income is that one fund. The fund managers can't possibly know what you receive from Social Security, a pension, or any other investments you might hold. Lifecycle funds should be considered as only one part of a complete retirement plan.