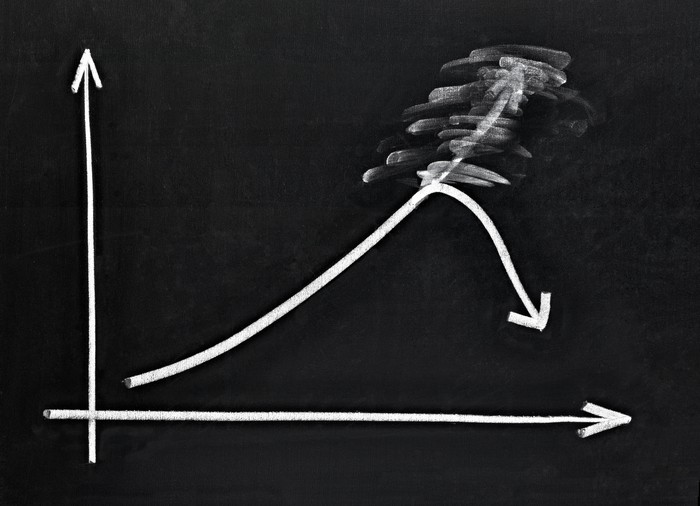

Deemed an essential business, Big Lots (BIG +0.00%) has kept its stores open during the coronavirus pandemic. But the company has been confronting sluggishness in sales and adjusted operating income for several years. In fiscal 2019, sales grew less than 2% year over year, from $5.2 billion to $5.3 billion, with same-store sales increasing a tepid 0.3%. Its adjusted operating income fell from $229 million to $207.9 million.

With this kind of performance, it's no wonder the stock's return has been negative over the last five years, lagging both the S&P 500 and S&P 500 Retail Indexes. This has drawn the interest of activist investors Macellum Advisors and Ancora Advisors, which own a combined 11.2% of the company and are seeking to replace the entire nine-member board of directors and improve capital allocation.

While Big Lots is fortunate to remain open during these trying times, the pandemic isn't the only issue that has weighed on the stock recently. The company was already off to a sluggish start in the first quarter when it reported fourth-quarter earnings at the end of February, before the widespread stay-at-home orders (although there were supply chain disruptions). This leads to the question of whether Big Lots is up for the challenges when we get back to the new normal.

Image source: Getty images.

A turnaround strategy

Management implemented Operation North Star in late 2018 and early 2019. There are three objectives: drive long-term profitable growth, fund the journey, and (by accomplishing the first two) create long-term shareholder value.

Driving long-term profitable growth has several components, including strengthening home offerings, increasing the number of stores, and growing e-commerce sales. Funding the journey involves reducing costs to invest in growth areas. While fully realizing these are long-term objectives, they have yet to show up in results. Fiscal 2019 comps were weak, and adjusted selling and administrative expenses rose slightly.

Perhaps the initiatives will pan out, but the company seems like it is confronting deeper issues.

Getting back to its roots

These stem from Big Lots getting away from its closeout roots by offering a Store of the Future format. Introduced in 2017, it emphasizes furniture, moving it to the front of the store, with seasonal and soft home goods on the side. Food and consumables were moved to the back of the store.

Things have not gone according to plan, and CFO Jonathan Ramsden stated on the fiscal fourth-quarter earnings call that, "Based on some recent softness in sales trends for our Store of the Future program, we have made a strategic decision to slow our rollout."

Granted, furniture, now accounting for approximately 27% of Big Lots' sales, was a strong sales performer, with a comps increase of 8.2% last year. The soft home category (16% of sales) saw a 1.7% comps rise, although comps for seasonal merchandise (15% of sales) fell by 0.1%.

It's just that this did not translate into higher profitability, with GAAP gross profit essentially staying flat at $2.1 billion and the gross margin contracting to 39.7% from 40.5%. Management attributed the lower gross margin largely to writing down inventory in the now-exited greeting card category along with markdowns and higher shrink (losses due to theft, administrative error, vendor fraud, damage, and cashier error).

I think successfully growing sales and profitability requires de-emphasizing the competitive furniture categories and placing greater importance on closeout merchandise, which Big Lots is known for and represents space where it has operated well. With the economy slowing down and a staggering number of layoffs over the last month, this could be a sweet spot for the company, providing ample opportunity to pick up goods and drive store traffic.

While a change in the board might prove beneficial, it is challenging to reinvigorate a retail business. The company did engage in a sale-leaseback transaction, which is expected to bring in $725 million, acquiescing in part to the activists' demands to monetize real estate. But this does not address the larger issue surrounding the merchandise strategy. Hence, I have serious reservations about management driving operational improvements and profitability, and investors should turn elsewhere.