An inverse ETF is an exchange-traded fund designed to produce returns that are the opposite of its underlying index or benchmark. Investors often use inverse ETFs in advanced investment strategies, serving to hedge existing positions or take a bearish stance in a certain market sector.

Inverse ETFs aren’t for everyone. These exchange-traded funds are generally best used for very short-term positions. If you think you might be able to use these investment vehicles to bolster your portfolio, read on to learn more.

What is an inverse ETF?

What is an inverse ETF?

An inverse ETF is an exchange-traded fund that uses financial derivatives to provide daily returns that are the opposite of the returns provided by the index or security it tracks.

For example, the ProShares Short S&P 500 ETF (SH 0.96%) holds swaps with various banks acting as the counterparty in a futures contract on the S&P 500.

That might sound like a bunch of jargon, but the idea is simple. If the S&P 500 index goes up, the fund must pay the daily return to the counterparties from its cash holdings. So the value of the fund will go down when the index goes up. Likewise, if the index declines, the banks will pay the fund, increasing its value.

Inverse ETFs are actively managed and use expensive financial instruments such as swaps, futures, and other derivatives. Those expenses are passed along to investors in the form of a high expense ratio.

A simple index fund, which will provide returns in line with its underlying benchmark, can provide that service for a minuscule fraction of a percentage point. For example, some S&P 500 index funds have an expense ratio as low as 0.015%. Meanwhile, a simple inverse ETF such as the ProShares Short S&P 500 ETF has an expense ratio of 0.89%. That means for every $1,000 you invest, you’ll pay $8.90 in fees per year, which can really eat away at your returns.

It’s also important to note that inverse ETFs produce their returns based on the daily change in the underlying security's value. Holding an inverse ETF for more than a day can produce returns that don't track with the total return of the underlying security. The more volatile the underlying security, the greater the tracking error.

Inverse ETFs vs. short selling

Inverse ETFs vs. short selling

An inverse ETF can produce similar results to short selling for investors. Short selling is when you borrow shares of a stock or other security from your broker and sell them with the goal of buying back the shares at a lower price later. As such, you can profit when prices of the shorted asset decline, similar to how an inverse ETF performs.

There are several key advantages of inverse ETFs over short selling for investors to know.

- Limited downside. Buying an inverse ETF means your downside is limited to the amount invested. The lowest price an inverse ETF can trade for is $0. If you short shares of an ETF, though, the price can go up indefinitely. You’ll be on the hook to buy back shares at some point. Your broker will likely alert you, prompting you to either add more cash to your account or cover your short sale before things get too out-of-hand. That’s known as a margin call.

- Trade in any account. Since short sales are done on margin -- i.e., a loan from your broker -- they’re not allowed in certain types of accounts. IRAs, for example, do not allow margin loans, so you couldn’t take a short position in the retirement account. You could, however, use an inverse ETF to accomplish something similar.

- Potentially lower fees. When an investor shorts a stock, they might pay a fee to borrow the shares on top of interest on the margin loan used to borrow them. There’s no fee to buy an inverse ETF, but they do charge high expense ratios.

A neutral point to consider is that a broker may be unable to obtain shares for an investor to short. Similarly, someone interested in a thinly traded leveraged ETF may find it difficult to buy or sell shares. If you're bearish on a small market sector, you may not have a practical choice between shorting an index fund and buying an inverse ETF.

A big disadvantage of inverse ETFs

A big disadvantage of inverse ETFs

Perhaps the biggest difference between inverse ETFs and short selling is the potential for volatility loss. Volatility loss describes the effect of volatility on total returns.

An investor can be directionally accurate in their assessment that the underlying security will decline in value but still lose money by investing in an inverse ETF. Here’s how:

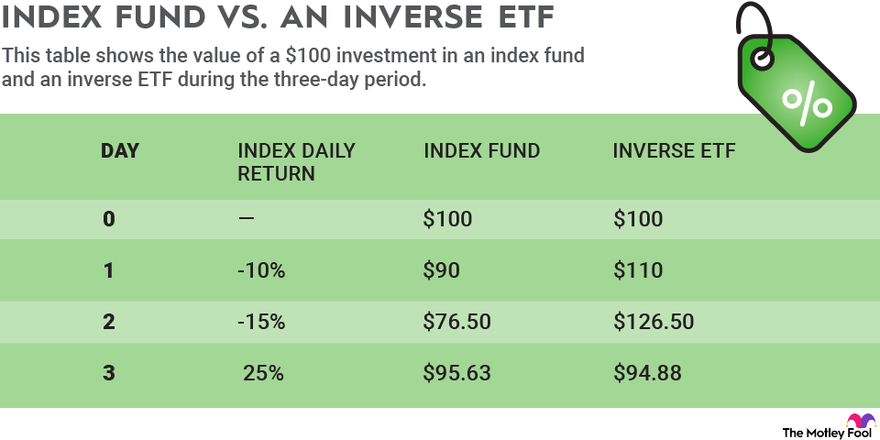

If the underlying security of an inverse ETF declines by 10% one day, the inverse ETF’s value will increase by 10%. The security might decline another 15% the next day but recover 25% the day after that. Over the three-day period, the security is still down more than 4% from its starting point.

Meanwhile, the inverse ETF is also down in value. That’s because while it gained 10% and 15% on the first and second days, respectively, it lost 25% of its value on the third day. In fact, it lost more value than the underlying security as a result of the significant volatility.

The table below shows the value of a $100 investment in an index fund and an inverse ETF during the three-day period.

If that investor had shorted the index by selling an ETF, they’d have generated a profit over that three-day period.

Leveraged ETFs use similar instruments as inverse ETFs. In fact, you can buy leveraged inverse ETFs. Be aware, however, that they can be very bad choices in volatile markets due to their potential for volatility loss. The mechanisms they use to provide inverse returns are only good for very short periods or periods where investors expect steady declines.

When should you buy an inverse ETF?

When should you buy an inverse ETF?

Inverse ETFs work best in the short term. Consequently, they’re best used as a short-term hedge on an existing position in your portfolio or to make a directional bet on the market.

For example, if you believe the Fed will announce an unexpected monetary policy at its next meeting that will send markets down, you can buy an inverse ETF around that meeting. (Note that this is pure speculation and isn’t advised.)

Perhaps you also hold a lot of tech stocks that are all set to report earnings around the same time. You might buy the Direxion Daily Technology Bear 3x Shares (TECS 6.24%) before they report and sell after the report to hedge your investments, putting a cap on the downside and upside of unexpected earnings results.

However, since the Direxion Daily Technology Bear 3x Shares is leveraged, you would likely only want to buy a small position in the ETF. That leverage also means that volatility loss could play a significant role in your overall results. So if the early results are bad but companies later report good earnings results, it could ruin your hedge.

Using inverse ETFs in your portfolio is an advanced strategy. It’s very important to know when to enter and exit a position in an inverse ETF because they can move against you very quickly. And, as previously mentioned, even if you’re directionally right, volatility loss can destroy your profits, so keep the holding period to a minimum.

Related investing topics

Do Inverse ETFs belong in your portfolio?

Do Inverse ETFs belong in your portfolio?

Inverse ETFs are very interesting financial vehicles, but most investors probably won’t be able to use them as part of a solid investment strategy. They’re most useful as a very short-term hedge due to the high expense ratios and the mechanisms used for providing inverse returns. It’s important to do your research and consider the potential upside and downside of putting your money in an inverse ETF.

Most investors will do well to simply buy an ETF that tracks a broad-based market index and charges a very low expense ratio. That simple strategy can produce great results with minimal effort.