Amortization and depreciation are non-cash expenses on a company's income statement. Depreciation represents the cost of using capital assets on the balance sheet over time, and amortization is the similar cost of using intangible assets, like goodwill, over time.

Asset

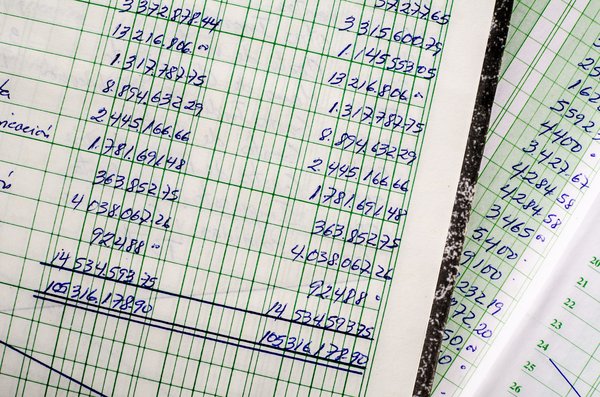

Calculating the proper expense amount for amortization and depreciation on an income statement varies from one specific situation to another. However, we can use a simple example to understand the basics.

The process

The process starts on the balance sheet and ends on the income statement

The accounting of amortization and depreciation is essentially the same. So, for our example, we can simplify the process and just consider a simple equipment purchase. Remember that an intangible asset would amortize in a very similar way over time, whether it's intellectual property, goodwill, or another account.

When a company buys a capital asset, such as equipment, it reports that asset on its balance sheet at its purchase price. Let's say our company buys a piece of equipment for $15,000. That means our equipment asset account increases by $15,000 on the balance sheet. Nothing has been reported on the income statement yet.

Over the next year, though, the company will begin to recognize a depreciation expense for the equipment, representing its gradual obsolescence, loss of value from use, and increased age. That expense, which appears on the income statement, is not for the full purchase price of the equipment but rather an incremental amount calculated from accounting formulas.

The first step in this calculation is determining which depreciation method to use to determine the proper expense amount. The simplest method is the straight-line method, where depreciation expense is constant over time as the equipment is used.

Other methods allow the company to recognize more depreciation expense earlier in the life of the asset. The key is for the company to have a consistent policy and well-defined procedures justifying the method. For simplicity, we'll use the straight-line method in this example.

First, the company must determine the asset's value at the end of its useful life. This salvage value, or residual value, is subtracted from the purchase price and then divided by the number of years in the asset's useful life. In the case of our equipment, the company expects a seven-year useful life, at which time the equipment will be worth $4,500, its residual value.

Completing the calculation, the purchase price ($15,000) minus the residual value ($4,500) is $10,500. Divided by seven years of useful life, this gives us an annual depreciation expense of $1,500. This will be the depreciation expense the company recognizes for the equipment every year for the next seven years.

Financials

How this calculation appears on the financial statements over time

For the next seven years, the company will recognize an annual depreciation expense of $1,500 on the income statement. At the same time, the book value of the equipment will reduce on the balance sheet by that same $1,500 per year. The reduction in book value is recorded via an account called accumulated depreciation. The chart below summarizes the seven-year accounting life of this equipment.

| Year | Depreciation Expense | Original Book Value | Accumulated Depreciation | NET Book Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Year 0: Purchase | $1,500 | $15,000 | $0 | $15,000 |

| Year 1 | $1,500 | $15,000 | $1,500 | $13,500 |

| Year 2 | $1,500 | $15,000 | $3,000 | $12,000 |

| Year 3 | $1,500 | $15,000 | $4,500 | $10,500 |

| Year 4 | $1,500 | $15,000 | $6,000 | $9,000 |

| Year 5 | $1,500 | $15,000 | $7,500 | $7,500 |

| Year 6 | $1,500 | $15,000 | $9,000 | $6,000 |

| Year 7 | $1,500 | $15,000 | $10,500 | $4,500 |

The income statement is hit with a $1,500 depreciation expense each year. That expense is offset on the balance sheet by the increase in accumulated depreciation, which reduces the equipment's net book value. As implied in the name of the straight-line method, this process is repeated in the same amounts every year.

Final thought

One final consideration on depreciation and amortization expenses

In strict terms, amortization and depreciation are non-cash expenses. In the example above, the company does not write a check each year for $1,500. Instead, amortization and depreciation are used to represent the economic cost of obsolescence, wear and tear, and the natural decline in an asset's value over time.

Related investing topics

However, while there may not be real cash expenses for amortization and depreciation each year, these are real expenses an analyst should pay attention to. For example, if the equipment purchased above is critical to the business, it will have to be replaced eventually for the company to operate. That purchase is a real cash event, even if it only comes once every seven or 10 years.

In many cases, treating amortization or depreciation as a non-cash event can be appropriate. However, the best analysts will first understand what is being amortized or depreciated, understand how those assets fit into the company's operations, and then make a conscious decision that makes the most sense for that specific situation in regard to the treatment of these expenses.

Need help navigating your way around an income statement? We have the tools to help you get started investing. Just head on over to our Broker Center.

This article is part of The Motley Fool's Knowledge Center, which was created based on the collected wisdom of a fantastic community of investors. We'd love to hear your questions, thoughts, and opinions on the Knowledge Center in general or this page in particular. Your input will help us help the world invest better! Email us at [email protected]. Thanks -- and Fool on!