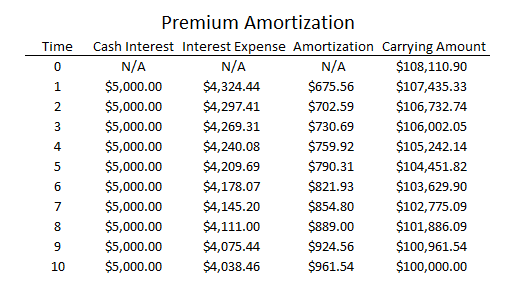

Bonds sold at a premium

Whereas the discount on a bond is recorded as additional interest expense, the premium on a bond is recorded as a reduction in interest expense.

Let's use the same example. Suppose XYZ Corp. issues $100,000 worth of bonds that pay a semiannual coupon of 5%, or 10% per year. These bonds are seen to be very attractive, and investors think the borrower is too good of a risk to pay 10% per year. Thus, the bonds sell at a yield to maturity of 8%, resulting in a premium.

The first step is to use a finance calculator to calculate how much the company will receive from selling these bonds by entering the following information into a financial calculator:

Future value: $100,000 (the face value of the bonds).

Number of periods: 10 (five years of semiannual payments).

Payment: $5,000 (5% semiannual coupon multiplied by the face value).

Rate: 4% (8% yield to maturity divided by two semiannual periods).

Solve for the present value.

You should find that the present value is $108,110.90. Thus, the bonds were sold at a premium of $8,110.90 ($108,110.90 in proceeds minus $100,000 in face value).

Interest expense calculations

To calculate interest expense on these bonds, we take the carrying amount of the bonds ($108,110.90) and multiply it by half the annual yield to maturity (8%/2=4%) to get $4,324.44 in interest expense.

Of course, the actual cash interest expense is still $5,000. However, the premium is amortized as a reduction to interest expense. Thus, interest expense is recorded as $4,324.44 for the first period, while $675.56 is recorded as premium amortization.

To calculate interest expense for the next semiannual payment, we subtract the amount of amortization from the bond's carrying value and multiply the new carrying value by half the yield to maturity. Here's what that looks like over the full five-year period.