There are many ways to evaluate a business. This includes the usual numbers from the operating statement like revenue, earnings, and margins, along with more obscure (but often useful) metrics like contracted backlog, funds from operations, dollar-based retention, and many, many others.

Different kinds of cash flow

Although cash flow cuts through a lot of the complexity of accounting to better understand a company's financial results, there are different measures of cash flow, depending on where it comes from (or goes towards). You can find these cash flow metrics – or the data to calculate them – on the financial statement called the statement of cash flows. Here are some examples, and where you find them on the cash flow statement:

- Cash flow from operations is the cash a company has left over (or has consumed in excess of) from sales after subtracting cash operating expenses. This is a useful measure of a company's ability to sustain its operations from its existing business without having to raise money via debt or stock sales.

- Cash flow from investing measures the cash impact of acquisitions, capital spending, and investment, like buying Treasuries with excess cash on the balance sheet. Conversely, when companies raise cash by selling assets or cashing in things like Treasury bills, they are also recorded here.

- Cash flow from financing is where a company records cash raised or spent on things like debt (secured and unsecured notes, revolving credit facilities, etc.) and secondary stock offerings or stock repurchases.

- Free cash flow is the gold standard for measuring a company's financial performance. Although it doesn't have its own spot on the cash flow statement, it's easy to calculate. The formula is cash from operations minus capital expenditures (purchases of property and equipment). This generally tells us how much cash the company generates that it's "free" to allocate how management sees fit after all necessary spending is covered.

By not including cash from financing or investing, the focus is on the operations that should be the primary source of cash. This helps deduct any financial engineering that can make ends meet temporarily, and the one-off benefits of things like asset sales. The result is what a company can deliver, not how smart its accounting team is.

Related investing topics

How to use cash flow to be a better investor

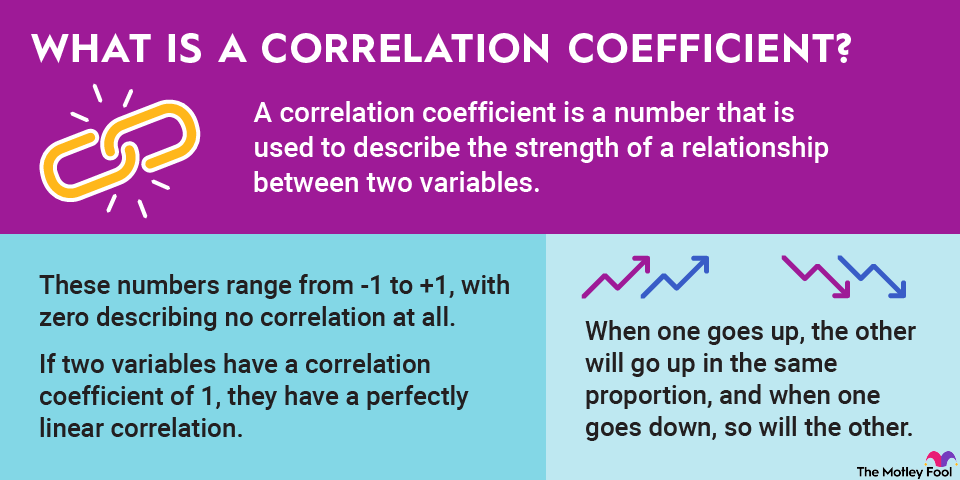

Although not a one-measure-fits-all metric, understanding cash flow will help you make better investment decisions. Because at the end of the day, it's cash that really matters; it's what companies pay their bills and employees with; it's what they charge their customers, and it's what you use to buy shares, and ideally get more of when you sell those shares. A company's ability to increase that cash flow – especially free cash flow – on a per-share basis, is almost directly correlated with the long-term results of its stock price. The companies that grow it, become more valuable; the ones that don't, well, don't.

It's also worth noting that free cash flow doesn't work well for every kind of business. Companies like banks, financial service providers, and insurers make a good bit of their money from a mix of fees from operations and income from investments. It can be more complicated to measure their cash flows. As is often the case, don't count on any single metric being the one that tells you everything about any company.

Put it all together, and understanding cash flows, where they come from, and whether a company is growing them (especially per-share) is one of the best steps you can take to get better at evaluating stocks.