Building a diversified portfolio of individual stocks and other assets can be a daunting task for any investor. A simple shortcut is to buy an index fund or mutual fund, which will invest your capital across a variety of securities.

While both index funds and mutual funds can provide you with the foundation of portfolio diversification, there are some important differences for investors to be aware of. So which is right for you? Let's take a look at index funds vs. mutual funds.

What are mutual funds?

A mutual fund pools money from lots of investors to buy a portfolio of securities designed to meet a goal. That goal is usually to outperform a benchmark index by selecting stocks, bonds, and other securities the fund manager believes will produce outsized returns.

When the manager actively selects which stocks to buy (and which ones not to), it's called an actively managed mutual fund. That stands in contrast to passively managed funds or index funds.

Buying a mutual fund is a bit different from buying a stock. A stock is listed on an exchange, and investors can buy or sell shares at any time. Any broker will have access to the major exchanges, and you'll be able to place a trade for a stock through your broker of choice.

Mutual funds are bought and sold through the mutual fund company itself. Brokers may have partnerships with some mutual fund companies or offer their own mutual funds, which allows their investors to buy shares of a mutual fund within their brokerage accounts. Sometimes, though, you'll have to go directly to a mutual fund company to buy shares. If you want to change your brokerage account, it may mean your mutual funds won't transfer to your new broker.

A mutual fund company collects inflows and outflows of investors' money throughout the day. Shares are marked to market at the end of the day based on net asset value -- the total value of all its holdings -- and investors who put in an order to buy or sell earlier in the day will get that price when shares trade hands after the markets close.

One feature of mutual funds is that you can typically buy fractional shares. While fractional shares of other securities are becoming common, it's actually a feature supported by individual brokers and not the securities themselves. You'll generally be able to acquire fractional shares of a mutual fund, which makes it convenient for someone looking to ensure all their money is invested or invest small amounts.

What are index funds?

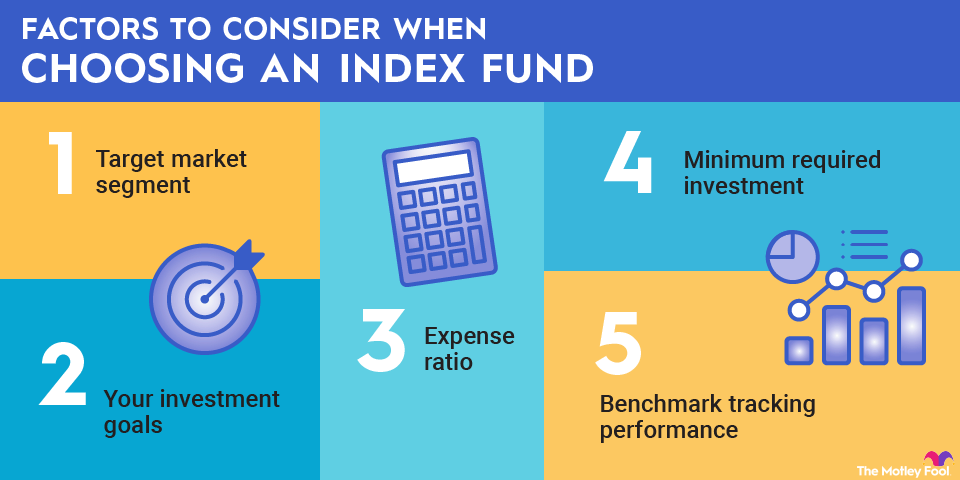

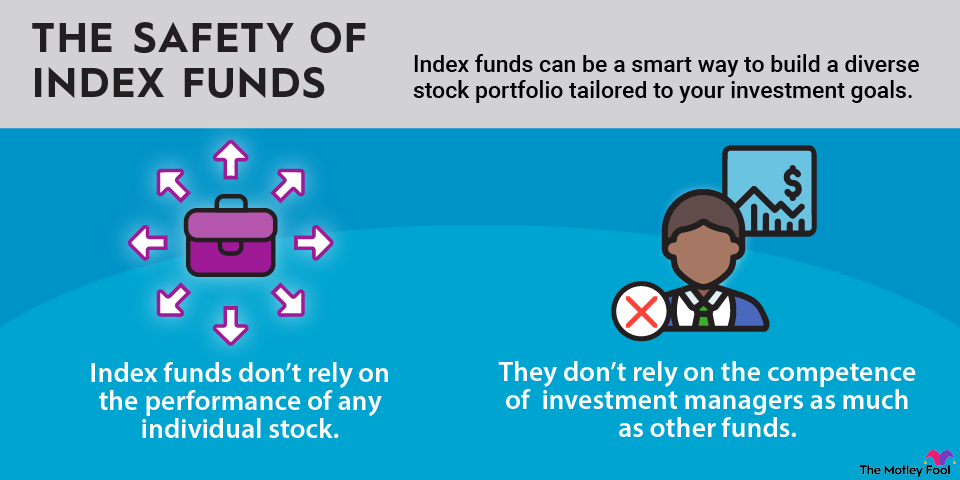

An index fund, much like a mutual fund, will pool investors' capital and buy a portfolio of securities. The difference, however, is that an index fund is a passively managed fund that merely aims to track a benchmark index's returns; an actively managed fund aims to outperform the benchmark index. An index fund manager buys the same securities that are tracked by the index with the same weightings.

An index fund can be structured as a mutual fund, in which case you'd buy and sell shares in the same way you would for any mutual fund.

Index funds may also be structured as exchange-traded funds, or ETFs. There are some subtle differences between ETFs and index funds that are structured as mutual funds. An exchange-traded fund, as the name implies, is traded on a stock exchange in the same way as a stock. Investors can buy and sell shares of an ETF throughout the day, and shares will likely be available to purchase through any broker you choose.

The drawbacks of an ETF include potentially paying a commission to your broker to buy shares. Also, you may not be able to buy fractional shares. That said, many brokers have gotten rid of commissions on simple purchases like ETFs, and more are also supporting fractional investing. Since shares trade on an exchange, they may trade at a premium or discount to the fund's net asset value.

Index funds vs. mutual funds

There are several differences between a passively managed index fund and an actively managed mutual fund. Here are the most important ones for investors to know before they decide which is best for them.

Goals

An index fund's sole purpose is to provide investors with exposure to a certain asset class. That could be large-cap U.S. stocks through a simple S&P 500 index fund. Or perhaps you have a more specific goal, like tracking the index of a certain sector such as financial stocks.

Index funds could also be part of a factor investing strategy where you seek exposure to something like small-cap value stocks. Importantly, the goal isn't to outperform the benchmark index its holdings are based on.

An actively managed fund will give you exposure to certain asset classes, but they'll also try to pick the best securities in those asset classes. For example, a large-cap U.S. stock mutual fund may look to outperform the S&P 500 by buying certain companies and overweighting in some sectors that the fund manager believes will outperform.

Unfortunately, most fund managers fail to outperform their benchmark index in any given year. In the 20 years from 2004 through 2024, 92% of fund managers underperformed the S&P 500. Picking the funds and managers that will outperform is practically impossible for investors since none have a consistent record of outperforming year after year.

Costs

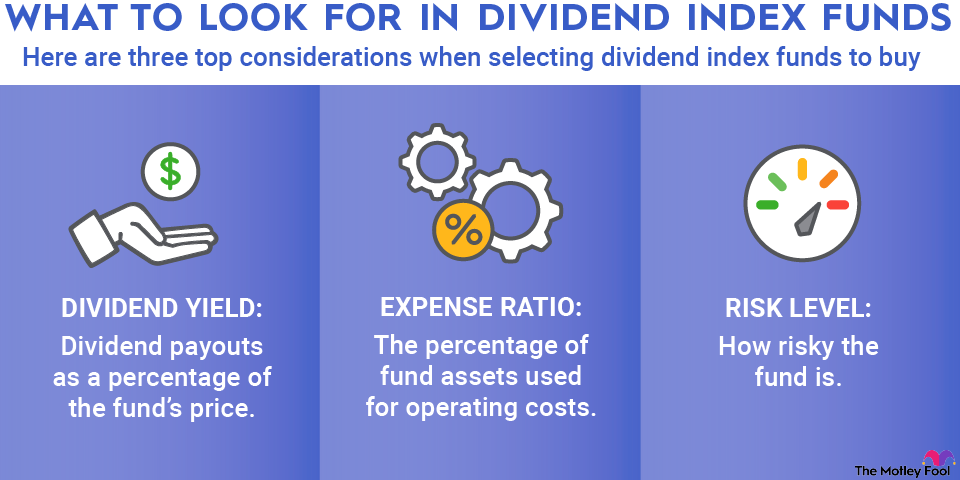

Both mutual funds and index funds make money by charging expense ratios, which are charged based on assets under management. For example, if you invested $10,000 with a mutual fund that charged a 1% expense ratio, you’d pay about $100 that year to invest your money. Of course, the nominal amount is always changing based on the fluctuating value of your portfolio, but expense ratios are generally very steady.

Since actively managed funds require a portfolio manager and a team of researchers to feed information about investment decisions, they charge higher expense ratios than index funds --sometimes 10 times higher. Many broad-based index funds have expense ratios of 0.10% or less.

If you purchase a mutual fund through a broker, you may also have to pay a sales load, which is a fee to compensate the broker. This could be paid up front (front-end load) or when the shares are redeemed (back-end load).

Taxes

Another cost to consider is that actively managed funds generally trade more frequently than passive index funds. That can trigger more taxable events for shareholders and create additional costs. What's more, shareholders have little control over those decisions despite being left with the tax bill.

Related investing topics

Which is right for you?

For most investors just starting out, an index fund will be their best choice. It's highly unlikely you'll be able to pick the fund manager who will outperform the index or sector you're looking to invest in.

Unless you have a good reason to pay the higher fees and expenses associated with actively managed mutual funds, investing in an index fund will likely accomplish exactly what you need as an investor.