If money makes the world go round, then economics is the study of how the world turns on its axis and the forces that influence that movement. It's also incredibly important for investors to have a basic understanding of economics as a better way to understand their investment decisions. Read on to learn more about this fascinating science.

What is economics?

Economics is a science that studies how different groups interact and intersect when it comes to limited resources. Generally, we think of economics as being the study of money, but it's really the study of anything valuable and the choices that are made about that valuable item.

When you study economics, you are not studying accounting, though there is some overlap. Economics combines subjects like accounting with psychology, politics, law, and business to create a more global understanding of how we make decisions about items that we consider valuable in our personal and professional lives.

Branches of economics

There are two primary branches of economics: microeconomics and macroeconomics. Each can be cut up into even more divisions, but these are the two main ways we think about economics.

Microeconomics examines economics from the perspective of the individual person or company. It's about how these individual players make their own decisions, how they use resources, and why they value what they value.

Macroeconomics, on the other hand, looks at entire systems of economic flow in a holistic way. Rather than looking at why a consumer buys one thing over another, we're examining why things like inflation occur or how unemployment affects the overall GDP of a nation.

Key economic concepts

There are four key economic concepts that help explain pretty much everything that happens in economics. How they interact and influence decisions is vital to understanding economics as a whole. These are:

- Scarcity. It's the most basic economic concept and one we all know well. Scarcity just states that there are limited resources that must somehow meet unlimited wants, which is impossible and sets up the entire need for the financial systems of the world.

- Supply and demand. Supply and demand drive markets and influence prices. On a very basic level, if there's a low supply and high demand, prices will rise; if there's a high supply and low demand, prices will fall.

- Costs and benefits. Economists generally believe that people are rational and seek to maximize their ratio of benefits to their costs. Of course, not every individual is rational, so this is not a perfect theory and helped spur the field of behavioral economics.

- Incentives. Incentives come in every form in an economic system. They're financial rewards for meeting increasing demand for a product, they're bonuses for workers to produce more products in a high-demand environment, and they're even benefits to customers for choosing one brand over another.

Expert views

Academic views on economics

Related investing topics

Why does economics matter to investors?

Economics is really all that matters to investors. Without an economic system, none of us would care about retirement planning or nest eggs, and we'd certainly not be investing in companies with the hope of making our money grow.

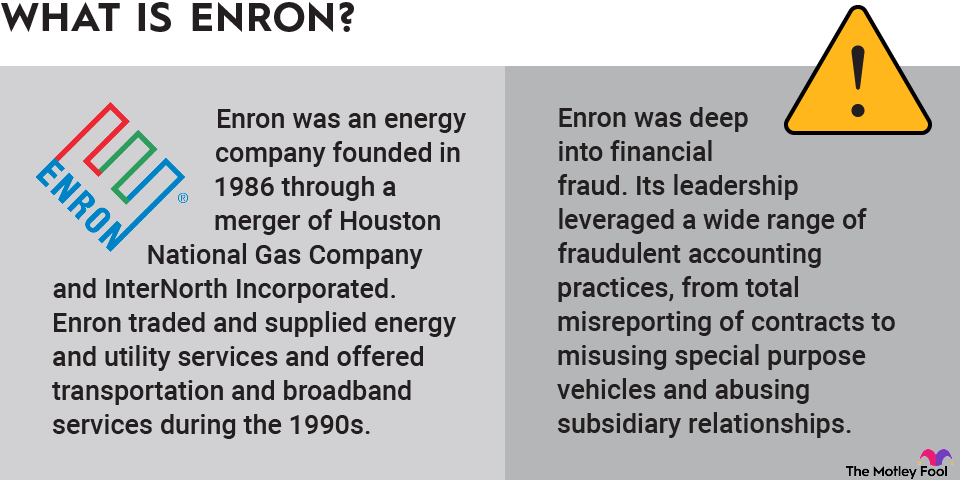

But beyond that, understanding economics is vital to investors so that we can better understand the environment in which the businesses we own stock in are operating, the needs and wants of the customers who use the products and services of the companies we've chosen to trust with our money, and what can possibly go wrong when we put our money into a company with x, y, and z characteristics.