Think of a closing entry as the period at the end of a long sentence. Every business in existence needs to close the books at the end of the accounting period, and the closing entry is the endpoint that wraps everything up. Whether it's monthly, quarterly, or annually, there's a process that ensures all the revenue and expenses are tallied up, and that’s where closing entries come in. Without them, the numbers don’t reset, and financial reports start piling on top of each other like an overstuffed inbox.

Let’s break down what a closing entry is, why it matters, and how to actually record one without feeling like you need a CPA on speed dial.

Understanding closing entries

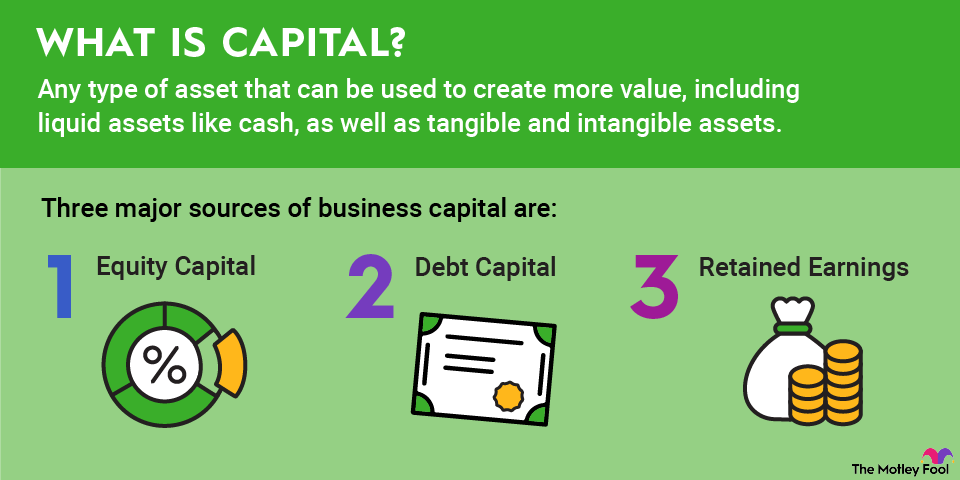

A closing entry is an accounting move that wraps up temporary accounts, like revenues, expenses, and dividends, so that they don’t carry over into the next accounting period. These accounts are zeroed out and moved into a permanent account called retained earnings (or sometimes into an income summary account first).

It’s a bit like clearing a scoreboard at the end of the game; you don’t carry over points from the last one, you start over with a fresh slate. This reset allows businesses to track income and expenses specific to each period, which is essential for good financial hygiene and accurate reporting.

Why closing entries matter

They keep financial records clean

Without closing entries, it’s possible for you to continuously stack up revenues and expenses in a perpetual, infinite Excel sheet indefinitely. Closing entries help avoid this type of financial mess by closing out temporary accounts and providing a clean slate for the next cycle. If you are trying to see how much you earned this month with parts of last quarter's income hovering around your books, then you can’t really get a full grasp of what’s going on month to month.

They help calculate retained earnings

The profits (or losses) from each period get rolled into retained earnings, which is important from both business operations and investor perspectives. This affects how much capital is available to reinvest, pay dividends, or just show the long-term value of the business. If you skip this step, your balance sheet won’t reflect reality.

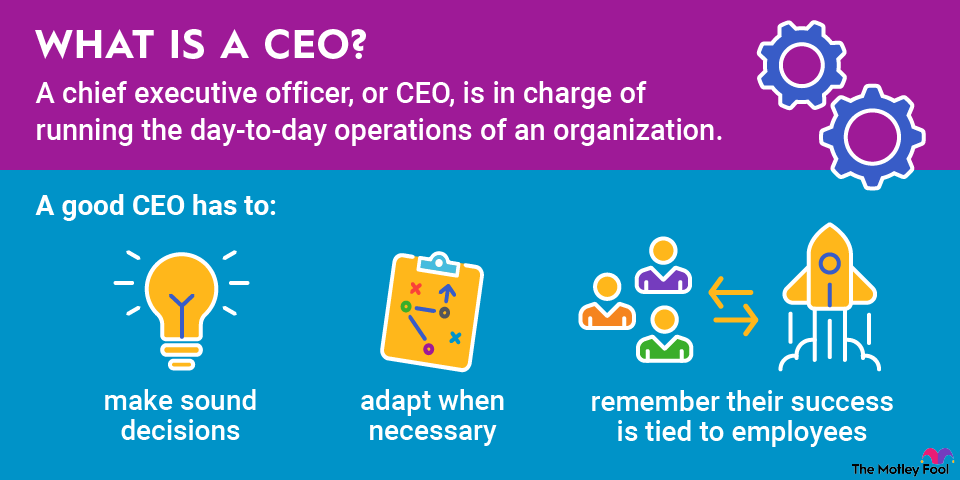

They make financial reporting make sense

Financial reporting is the name of the game when it comes to investor transparency, and any publicly traded company will attest to the reporting hoops that the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) requires them to jump through to maintain their public listing.

How to record and use a closed entry

To close out your books at the end of the year (or month), you start by clearing out your revenue accounts. This means taking all the income your business earned and moving it into a holding account, which for many accountants is referred to as an “income summary.” So, if you made $100,000, you’d record that as a debit from revenue and a credit to income summary. Think of it like transferring all your “money earned” into a single tally sheet before you figure out the final score.

Next, you do the same with your expenses by adding up everything you spent on supplies, rent, marketing, and so on. You move that total into the income summary account. If your total expenses were $70,000, you’d debit the income summary and credit your expense account. What you’re left with in the income summary is your profit or loss. You then take that final number and shift it over to your retained earnings, basically the company’s “savings” account. So if you had a profit of $30,000, that gets added to your retained earnings; if it was a loss, the amount comes out of it.

And finally, if you paid out any dividends (say, to yourself or shareholders), that gets subtracted from retained earnings, too. For example, if you paid $5,000 in dividends, you’d reduce retained earnings accordingly. When all that’s done, your temporary accounts (revenue, expenses, dividends) are cleared out, and your books are ready for a fresh start in the new period.

Related investing topics

Real-world example: A small business at year-end

Let’s say Maria runs a small graphic design business called Maridesign. At the end of the year, her income statement shows $120,000 in revenue and $85,000 in expenses. She also paid herself a $10,000 dividend.

Here’s what her closing entries would look like:

Account | Debit | Credit |

|---|---|---|

Revenue | $120,000 | – |

Income Summary | – | $120,000 |

Income Summary | $85,000 | – |

Expenses | – | $85,000 |

Income Summary | $35,000 | – |

Retained Earnings | – | $35,000 |

Retained Earnings | $10,000 | – |

Dividends | – | $10,000 |

After this, Maria’s revenue and expense accounts are at zero, and her retained earnings show a net increase of $25,000 ($35,000 profit minus $10,000 in dividends). Her books are now ready for a fresh start next year.