A capital gain is any profit from the sale of a stock, and it has unique tax implications. If you sell stock for more than you originally paid for it, you may have to pay taxes on your profits.

Here's what you need to know about selling stock and the taxes you may have to pay.

How to calculate profits from selling stock

When you sell stock, you're responsible for paying taxes only on the profits -- not on the entire value of the sale.

To determine profits, take your total proceeds and subtract your cost basis (also known as your tax basis), which consists of the amount you paid to buy the stock in the first place plus any commissions or fees you paid to buy and sell the shares.

Cost basis = Price paid for stock + Commission and fees

Profits = Proceeds from sale - Cost basis

Example of how to calculate profits from a stock sale

Let's say you bought 10 shares of stock in Company X for $10 each and paid $5 in transaction fees for the purchase. If you later sold all the stock for $150 total, paying another $5 in transaction fees for the sale, here's how you'd calculate your profits:

Cost basis = $100 (10 shares @ $10 each) + $10 (purchase and sale fees @ $5 each) = $110

Profits = $150 - $110 = $40

So, in this example, you'd pay taxes on the $40 in profits, not the entire $150 total sale price.

Now that you've determined your profits, you can calculate the tax you'll have to pay. The taxes you owe depend on your total income for the year and the length of time you held the shares.

Short-term and long-term capital gains taxes

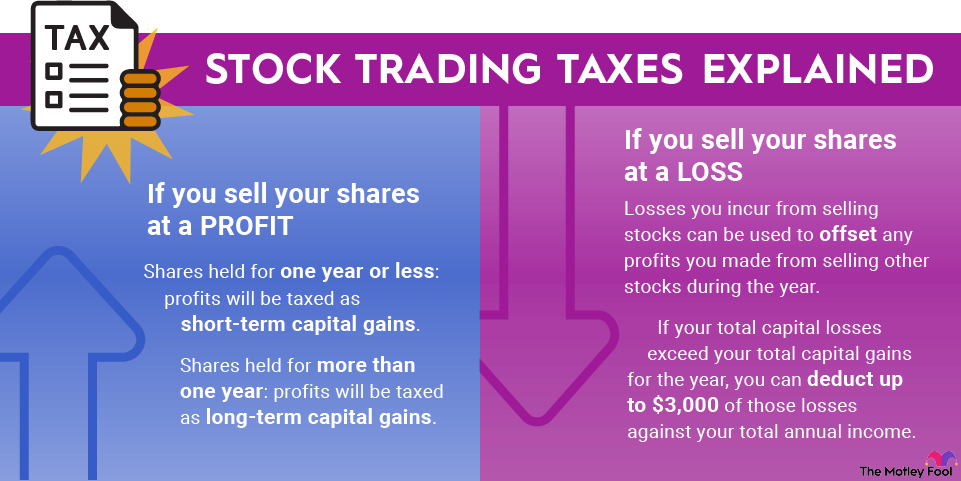

Generally speaking, if you held your shares for one year or less, then profits from the sale will be taxed as short-term capital gains. If you held your shares for more than one year before selling them, the profits will be taxed at the lower long-term capital gains rate.

Capital Gains Tax

Both short-term and long-term capital gains tax rates are determined by your overall taxable income. Your short-term capital gains are taxed at the same rate as your marginal income tax rate (tax bracket). You can get an idea from the IRS of what your tax bracket might be for 2025.

For the 2025 tax year (i.e., the taxes most individuals filed by April 15, 2026), long-term capital gains rates are either 0%, 15%, or 20%. Unlike past years, the break points for these levels don't correspond exactly to the breaks between tax brackets:

Long-Term Capital Gains Tax Rate | Single Filers (Taxable Income) | Married Filing Jointly/Qualifying Surviving Spouse | Head of Household | Married Filing Separately |

|---|---|---|---|---|

0% | Up to $48,350 | Up to $96,700 | Up to $64,750 | Up to $48,350 |

15% | $48,351-$533,400 | $96,7001-$600,050 | $64,751-$566,700 | $48,351-$300,000 |

20% | Over $533,400 | Over $600,050 | Over $566,700 | Over $300,000 |

To calculate your tax liability for selling stock, first determine your profit. If you held the stock for less than a year, multiply by your marginal tax rate. If you held it for more than a year, multiply by the capital gains rate percentage in the table above.

But what if the profits from your long-term stock sales push your income to a higher bracket? This is sometimes known as the "bump zone." Since capital gains rates are marginal, like ordinary income tax rates, you'd pay the higher rate only on the capital gains that caused your income to exceed the threshold. Remember that capital gains are not limited only to stock sales; they affect any sales of investment assets, including real estate.

Example of long-term capital gains tax

Let's say you and your spouse make $50,000 of ordinary taxable income in 2025, and you sell $150,000 worth of stock that you've held for more than a year. The gains on the sale total $100,000. You'll pay taxes on your ordinary income first and then pay a 0% capital gains rate on the first $46,700 in gains because that portion of your total income is below $96,700. The remaining $53,300 of gains are taxed at the 15% tax rate.

How to avoid paying taxes when you sell stock

One way to avoid paying taxes on stock sales is to sell your shares at a loss. Although losing money certainly isn't ideal, losses you incur from selling stocks can be used to offset any profits you make from selling other stocks during the year. If your total capital losses exceed your total capital gains for the year, you can deduct as much as $3,000 of losses against your total income for the year. You can carry any additional losses into the following tax year.

However, you can't sell a bunch of shares at a loss to lower your tax bill and then turn around and buy them right back again. The IRS doesn't allow this kind of "wash sale" -- called by this term because the net effect on your assets is "a wash" -- to reduce your tax liability. If you repurchase the same or "substantially similar" stocks within 30 days of the initial sale, it counts as a "wash sale" and can't be deducted.

Of course, if you end the year in the 0% long-term capital gains bracket, you'll owe the government nothing on your stock sales. The only other way to avoid tax liability when you sell stock is to buy stocks in a tax-advantaged retirement account.

Related investing topics

Using a tax-advantaged stock account

A tax-advantaged account is an investment account such as a 401(k), 403(b), or traditional IRA.

In these accounts, your contributions may be tax-deductible, but your qualified withdrawals will typically count as income. Roth accounts, on the other hand, are tax-free investment accounts. You can't get a tax deduction for contributing, but none of your qualified withdrawals will count as taxable income.

With any of these accounts, you will not be responsible for paying tax on capital gains -- or on dividends, for that matter -- so long as you keep the money in the account. The drawback is that these are retirement accounts, so you are generally expected to leave your money alone until you turn 59 1/2.