Stock investing means putting your money to work in publicly traded companies. By investing in a stock, you get slices of ownership in a company, and you are entitled to benefit from its future profits. Stock investing can allow you to own a piece of your favorite retailers, software providers, and much more.

When done correctly, investing in stocks is one of the most effective ways to build long-term wealth. But like most financial decisions, there are right ways and wrong ways to invest in the stock market. With that in mind, here's a step-by-step guide to investing money in the stock market correctly.

1. Determine your investing approach

The first thing to consider is how to start investing in stocks the right way for you. Some investors buy individual stocks, while others take a more passive approach with mutual funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs, more on those in a bit). Both can be equally valid ways to invest your money. Try this. Which of the following statements describes you?

- I'm an analytical person who enjoys crunching numbers and doing research.

- I hate math and don't want to do a ton of homework.

- I have several hours each week to dedicate to stock market investing.

- I enjoy reading about various companies I can invest in, but I don't have any interest in delving into math-related topics.

- I'm a busy professional and don't have the time to learn how to analyze stocks.

No matter which of these statements you agree with, you're probably a good candidate to become a stock market investor. The only thing that will change is how you do it.

The different ways to invest in the stock market

Individual stocks

You should invest in individual stocks if -- and only if -- you have the time and desire to thoroughly research and evaluate stocks on an ongoing basis. If this is the case, we 100% encourage you to do so.

On the other hand, maybe quarterly earnings reports and moderate mathematical calculations don't sound appealing. In that case, there's absolutely nothing wrong with taking a more passive approach.

Index funds

If you'd like to play a role in your investment decisions but don't necessarily want to choose individual stocks, you can invest in index funds. These track a benchmark index, such as the S&P 500. Index funds typically have low costs and are virtually guaranteed to match the long-term performance of their underlying indexes, minus some small investment fees.

Robo-advisors

Does putting your stock investing on autopilot sound like the best choice for you? One option that has exploded in popularity in recent years is the robo-advisor.

Robo Advisor

A robo-advisor, also known as an automated investing platform, is a brokerage that invests on your behalf in a portfolio of index funds appropriate for your age, risk tolerance, and investing goals. Not only can a robo-advisor select your investments, but many will also optimize your tax efficiency and make changes over time automatically.

2. Decide how much money you will invest in stocks

First, let's talk about the money you shouldn't invest in stocks. In simple terms, the stock market is no place for money you might need within the next five years, at a minimum. Money you need to pay your kids' tuition or pay day-to-day expenses in retirement should be kept in less-volatile investment vehicles.

The stock market is likely to rise over the long term. However, there's simply too much uncertainty in stock prices in the short term. In fact, a drawdown of 20% in any given year isn't unusual, and occasional drops of 40% or even more do happen. Stock market volatility is normal and should be expected. So, here's what money you shouldn't be investing:

- Your emergency fund

- The money you'll need to make your child's next few tuition payments

- Next year's vacation fund

- Money you're saving for a down payment on a home

Asset allocation

How you distribute your investable money is a concept known as asset allocation. Several factors come into play here. Your age is a significant consideration, as are your specific risk tolerance and investment objectives.

Let's start with your age. The general idea is that, as you get older, stocks become a less desirable place to keep your money. If you're young, you have decades ahead of you to ride out any ups and downs in the stock market. This isn't the case if you're retired and rely on your investments for income.

Here's a quick guideline, known as the Rule of 110, to help you establish a ballpark asset allocation. To use it, start by simply subtracting your age from 110.

This is the approximate percentage of your investable money that should be in stocks (including mutual funds and exchange-traded funds (ETFs) that are stock-based). The remainder should be in fixed-income investments, such as bonds or high-yield certificates of deposit (CDs).

For example, let's say you are 40 years old. This rule suggests that 70% of your investable money should be allocated to stocks, with the other 30% in fixed-income investments, such as bonds or high-yield CDs.

3. Open an investment account

All the advice about investing in stocks for beginners doesn't do you much good if you don't have any way to actually buy stocks. To do this, you'll need a specialized type of account called a brokerage account.

These accounts are offered by companies such as Charles Schwab (SCHW -1.80%), E*TRADE from Morgan Stanley (MS -2.21%), and many others, as well as by newer app-based platforms, including Robinhood (HOOD +0.70%) and SoFi (SOFI -0.92%).

Opening a brokerage account is typically a quick and painless process that takes only minutes. And most will allow you to invest with play money first to make sure the platform is a good fit for you.

You can easily fund your brokerage account via an electronic funds transfer, by mailing a check, or by wiring money. Opening a brokerage account is generally easy, but you should consider a few things before choosing a particular broker:

Type of account

First, determine the type of brokerage account you need. For most people who are just trying to learn stock market investing, this means choosing between a standard brokerage account and an individual retirement account (IRA).

Both account types will allow you to buy stocks, mutual funds, and ETFs. The primary considerations here are why you're investing in stocks and how easily you want to access your money. If you want easy access to your money or are just investing for a rainy day, you'll probably want a standard brokerage account.

On the other hand, if your goal is to build up a retirement nest egg, an IRA is a great way to go. These accounts come in two main varieties -- traditional and Roth IRAs -- and there are some specialized types of IRAs for self-employed people and small business owners, including the SEP-IRA and SIMPLE IRA.

A key point is that IRAs are highly tax-advantaged vehicles for purchasing stocks. However, the downside is that it can be difficult to withdraw your money until you reach a certain age.

There are also specific qualifications for investing in IRAs and taking the tax benefits, such as the Roth IRA income limits, so be sure to qualify before investing. One potentially appealing feature of Roth IRAs is the ability to withdraw your contributions (but not your investment profits) at any time and for any reason.

Costs and features

The majority of online stockbrokers have eliminated trading commissions for online stock trades. So, most (but not all) are on a level playing field as far as costs are concerned, unless you're trading options or cryptocurrencies, both of which often have trading fees. However, there are several other big differences.

For example, some brokers offer customers a variety of educational tools. Some offer access to investment research and other features that are especially useful for newer investors. Some have physical branch networks, which can be beneficial if you prefer face-to-face investment guidance.

There's also the user-friendliness and functionality of the broker's trading platform to consider. Many will let you try a demo version before committing any money; if that's the case, it can be well worth the time.

4. Choose your stocks

We've answered the question of how you buy stocks. If you're looking for some great beginner-friendly investment ideas, here is a list of some of our top stocks to buy and hold to help get you started. Note that this isn't intended as personal advice -- just some well-run businesses to help get your search started.

Of course, in just a few paragraphs, we can't go over everything you should consider when selecting and analyzing stocks. However, here are the important concepts to master before you get started:

- Diversify your portfolio.

- Invest only in businesses you understand.

- Avoid high-volatility stocks until you get the hang of investing.

- Always avoid penny stocks.

- Learn the basic metrics and concepts for evaluating stocks.

It's a good idea to learn the concept of diversification, which means you should have a variety of different types of companies in your portfolio. That said, I'd caution against too much diversification.

Stick with businesses you understand -- and if it turns out that you're good at (or comfortable with) evaluating a particular type of stock, there's nothing wrong with one industry making up a relatively large segment of your portfolio.

If you want to invest in individual stocks, it is essential to familiarize yourself with some of the basic methods for evaluating them. Our guide to value investing is a great starting point. There, we help you find stocks trading for attractive valuations.

5. Continue investing

Here's one of the biggest secrets of investing, courtesy of the Oracle of Omaha himself, Warren Buffett: You don't need to do extraordinary things to achieve extraordinary results.

The most surefire way to make money in the stock market is to buy shares of great businesses at reasonable prices and hold on to the shares for as long as the businesses remain great (or until you need the money). If you do this, you'll experience some volatility along the way. But over time, you'll most likely enjoy excellent investment returns.

Types of stocks

There are literally hundreds of categories and subcategories of stocks. Here are some of the common categories investors should be familiar with:

- Common stocks: Stocks that allow you to own equity in a business

- Preferred stocks: Stocks that have a guaranteed rate of return and work like debt instruments, not equity investments

- Growth stocks: Companies that are growing sales faster than the overall stock market average

- Value stocks: Companies whose stocks are (theoretically) trading for a discount to the intrinsic value of the business

- Dividend stocks: Stocks that pay regular distributions of cash to investors

- Large-cap stocks: Generally used to refer to companies with a $10 billion market cap or higher

- Mid-cap stocks: A company with a market cap of between $2 billion and $10 billion

- Small-cap stocks: Companies with less than $2 billion in market cap

Potential benefits and risks of investing in stocks

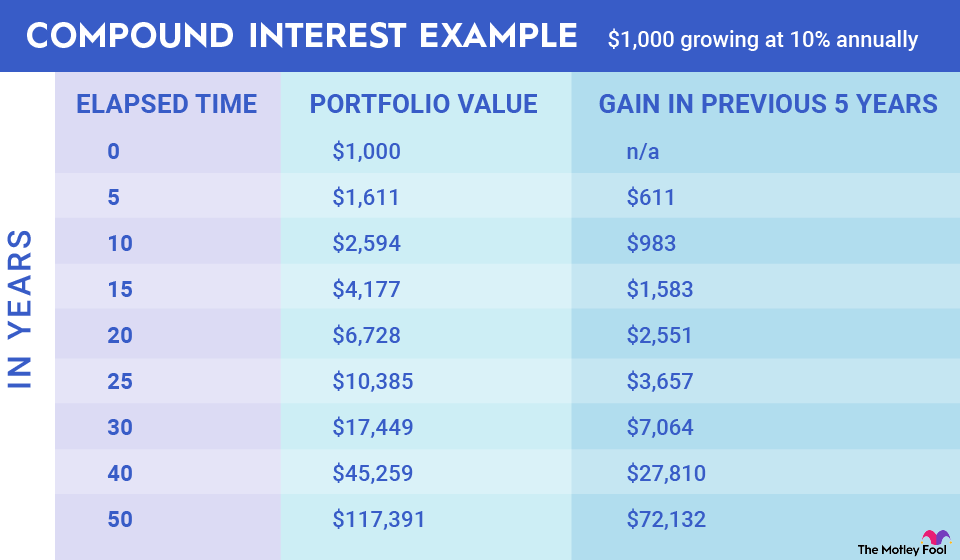

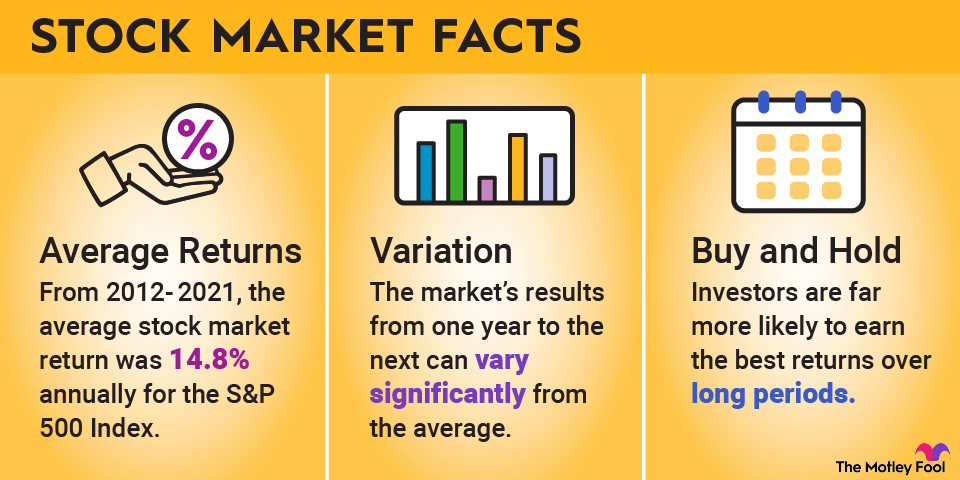

As mentioned, stocks can be a great way to create wealth over time. Over several decades, major stock market averages have consistently produced returns of between 9% and 10% annually.

Think of it this way. Based on an expected 10% long-term rate of return, if you invest $5,000 in stocks every year for 30 years, you would have a nest egg worth more than $900,000. There are other benefits of investing in stocks as well:

- Inflation protection: As a whole, the stock market has historically been an excellent hedge against inflation.

- Income: Many stocks pay dividends, and some are extremely consistent. Dividend stocks can be a great way to create a passive income stream.

- Liquidity: Stocks are highly liquid assets, which means that you can readily buy and sell them at full market value whenever you want (or at least whenever the market is open).

The primary risks are associated with the volatility of stocks over short periods of time. Swings of 10% in the stock market are relatively common, occurring approximately once a year, and declines of 20% or greater (which define a bear market) happen occasionally.

It's also important to emphasize that when investing in stocks (especially individual companies), you can lose money. Here are some of the reasons a stock investment could potentially turn sour:

- Competitors taking market share

- Interest rate fluctuations (depending on the nature of the business)

- Political headwinds that affect a business or entire industry

- Inflation

- Geopolitical tensions, such as trade wars and tariffs

- Negative news about a specific business

Stock investing mistakes to avoid

There are many potential mistakes new stock investors can make, and here are some of the most common. Avoiding these can save you a lot of money and aggravation as you build your investment portfolio:

- Don't make emotional investing decisions. Our instincts tell us to put our money into stocks when they're going up and we see everyone else making money and to sell before things get any worse when stocks are going down. This is literally the opposite of the buy low, sell high principle, the central goal of investing.

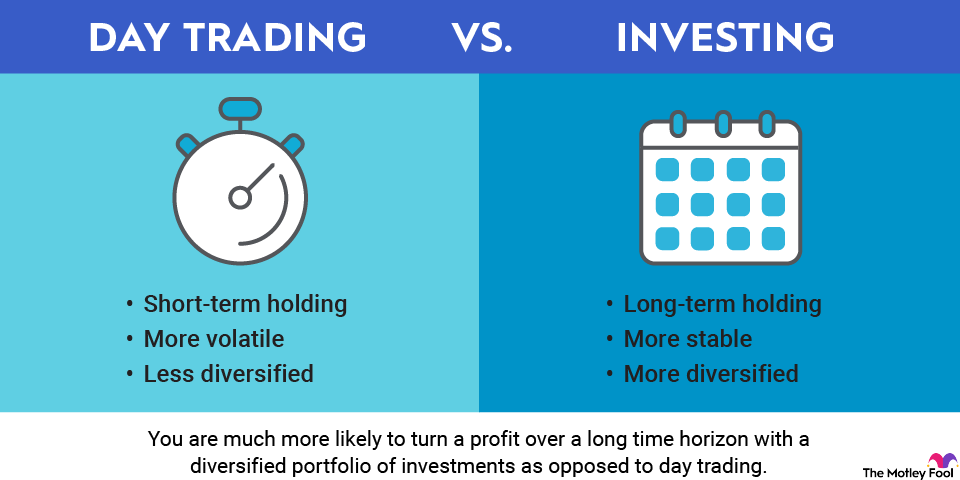

- Don't day trade or try to buy stocks because you think prices are about to go up. Leave short-term trading to professionals.

- Don't invest on margin (borrowed money). Not only will you pay interest on the money you borrow, but if your stocks fall, this can also magnify your losses.

- Don't use options to invest. Options should be left to those with more experience, at least until you really know what you're doing.

Related investing topics

Creating a well-balanced stock portfolio

It's important -- especially when you're just getting started with investing -- to not put too much of your money into a single company or even a single industry. The goal should be to create a diversified stock portfolio. Different experts have different definitions of diversification, but as a general rule, it's wise to aim for a portfolio of at least 25 stocks in a variety of industries.

Now, this doesn't mean you have to own stocks from every industry. If you aren't comfortable evaluating, say, pharmaceutical stocks, it's completely fine to avoid them. But the point is that you don't want the bulk of your money invested in financial stocks, artificial intelligence (AI) stocks, or any other single type of business.